Diagnosing what students need

When visiting a doctor, you often get a diagnosis and your doctors will begin to put a plan for treatment based on that diagnosis. As we begin to think of how we address the learning loss that has happened due to COVID-19, we should think about using student diagnostics to create a learning plan for students. Educators could use diagnostics to start the 2021 school year, understand how much learning loss has occurred, and be given the supports to develop learning plans and formative diagnostics for their students, all with a goal to get students to or above grade level. This would then require school systems to create the supports and resources necessary for teachers to reflect on the data and create student action plans. Student learning can then be calibrated with diagnostic information and formative and summative data.

Redesigning student diagnostics

The passage of the federal No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 brought a strong focus on state accountability and performance systems with clear penalties and interventions. Student performance data began to drive conversations about teacher performance and evaluation, school closures and reconstitutions, school ratings, school funding, and superintendent evaluations. One of the lasting effects of No Child Left Behind has been the annual ritual of spring summative state assessments that have been used to ring the alarm on schools that are “underperforming,” or in some instances, to “evaluate” teachers’ performance. The results of these summative assessments, paired with the reduction of human capital in school systems, has made it difficult to create a culture that focuses on student learning.

The inescapable back and forth about whether spring assessments will move forward in 2021 (Secretary Devos insisted they would, but Secretary Cardona could reverse that decision) leads me to question how much we truly value student learning. I often reflect on students from Southeast Los Angeles, the community I was raised in, and I’m aware of the challenges our students face today. From technology challenges, to conducive learning environments, to adult supports, our students lack the basic needs to have an opportunity to learn. In many communities, COVID-19 has essentially shut down schools, and students that have missed out on opportunities to learn should not be required to take end-of-year assessments that will be used for accountability purposes. What will a state summative assessment this year shed light on? Instead, could we use the fact that students will have experienced significant learning loss to redesign how we use testing? How would we design an assessment system that educators can use to help students that have lost opportunities to learn for whatever reason along the way? Specifically, could we start using assessments as a diagnosis for students’ learning? After all, improving science literature originates in the medical field and is extremely applicable to how we should view student learning.

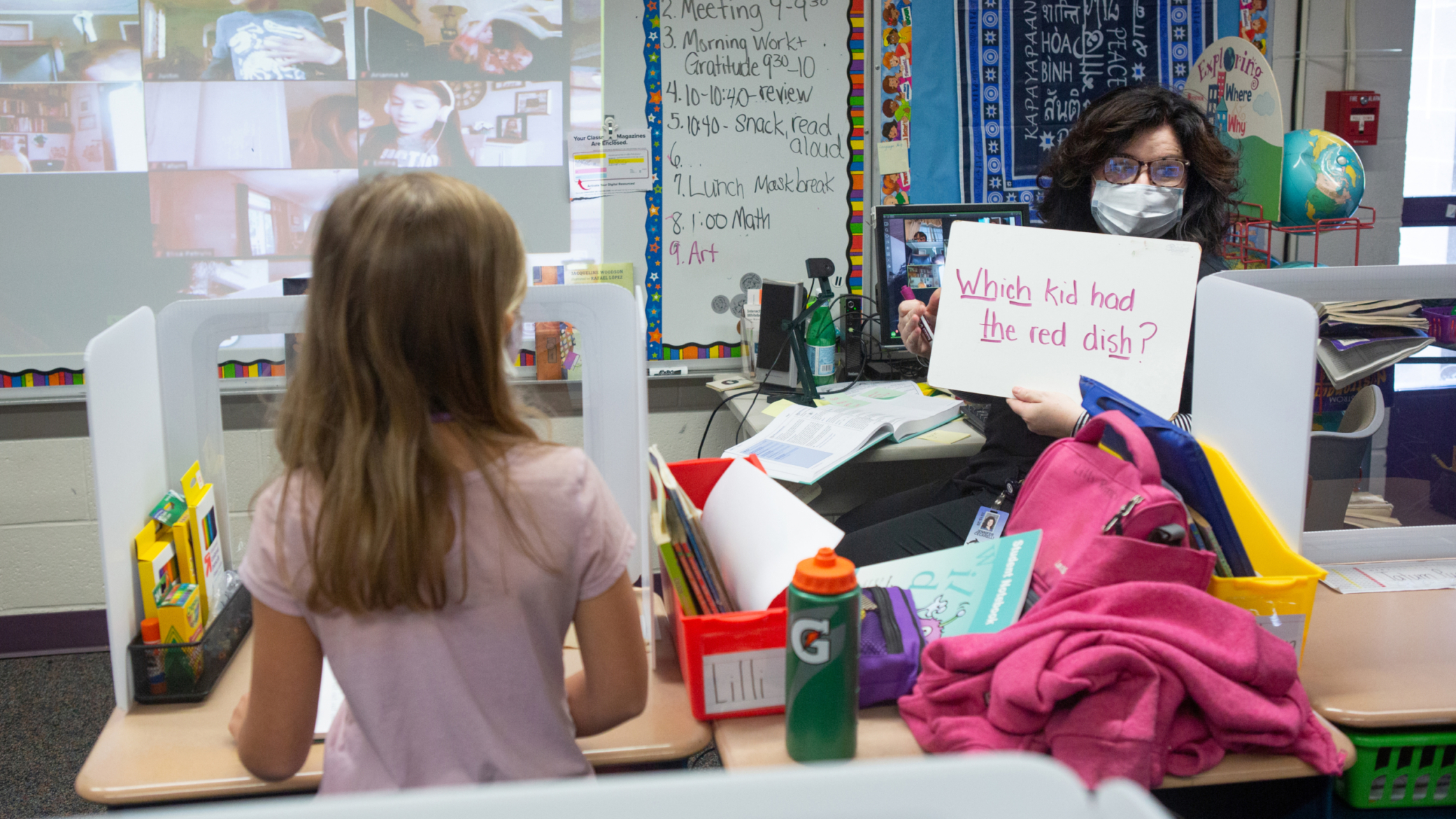

A recent survey of over 20,000 students in 166 schools across nine states by YouthTruth revealed that once schools were closed and moved to distance learning, only half of the students reported receiving assignments that really helped them. Students who thrived were self-motivated and preferred outcomes-based assignments, setting their own pace, and having control over their time. The goal should be to focus on teaching and learning. The goal should be to get back to providing educators with the data and supports they need to improve student learning and student outcomes. We should be using the time to create state diagnostic assessments that school systems can use to understand the learning. Every student should have the opportunity to take a diagnostic that provides educators with a comprehensive picture of students’ performance levels. State departments of education and school systems should begin to build resources and tools for educators to support student learning. Diagnostics should be calibrated to learning standards and have built-in formative assessments for educators to understand how students are progressing as the year continues. Lastly, as we transition students back into classrooms, we should take stock of how devices and online content can be utilized as a tool to enhance student learning and not lose the innovation brought to us by the pandemic.

In a time when students experienced interrupted learning at the end of the 2019-2020 school year and have experienced challenges in getting the 2020-2021 school year up and running, it is reasonable to conclude that students have not had the opportunity to learn and the effects of the pandemic impact on learning are unknown. Now would be the time to begin to rethink how we diagnose students’ learning needs and use them to craft instructional plans that address students’ instructional needs.