What if classrooms were rooted in care?

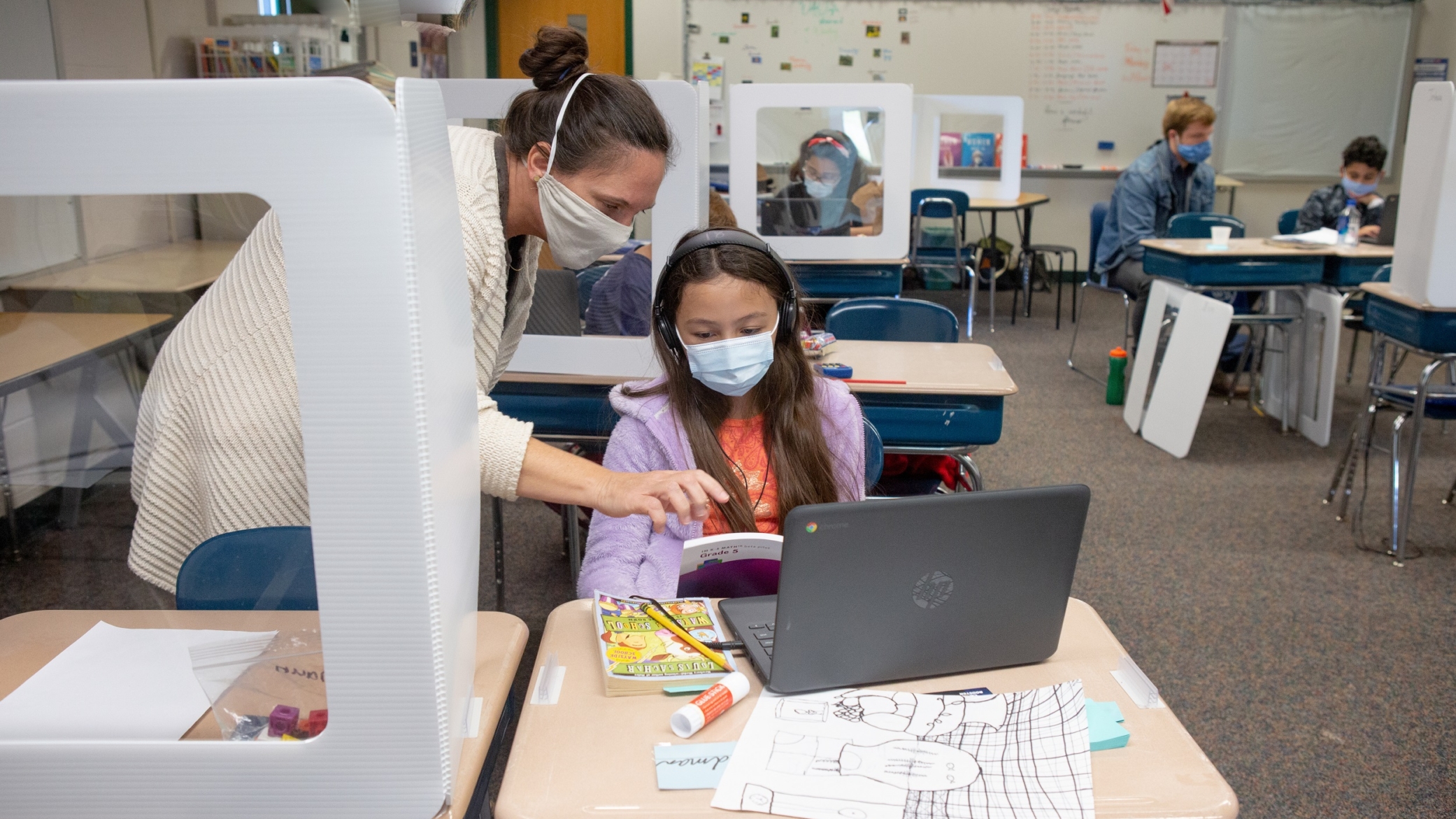

Building that sense of connection with students is no less important as they grow. Particularly now, educators need to prioritize listening to learners. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted what school looks like and more clearly revealed the deeply entrenched systemic inequities in school systems. There is no doubt that schools need to change, and in some ways the current crisis in education has provided a new starting point for learners. Going back to what “normal” used to be is not safe or supportive for many students. At the same time, we cannot presume to know what every student is experiencing or needs right now.

For example, at a time when so many adults are decrying “learning loss” and imperfect homework assignments, we have only to listen to students to hear that there may be a lot going well in education right now. YouthTruth’s Spring 2020 survey, which included 20,000 students from 166 schools in nine states, asked students about their experiences learning at home and how their schools could help. True, students struggled with distractions at home, stress with having to care for family members, and staying motivated with fewer opportunities to connect with their friends and teachers. But it wasn’t all bad. Some students appreciated having the flexibility to learn at their own pace, take breaks when they need to, exercise more, and be closer to their families. Students spoke to how they were learning to care for their own wellbeing and for the wellbeing of others, to manage their time under different constraints, and their desire for greater agency in how they learn.