Verify 2023: Navigating AI and cybersecurity challenges

The impact of collaboration in establishing new frameworks, fighting authoritarian regimes, and tackling complex cybersecurity challenges was consistently highlighted throughout the three-day event. In the conference’s opening night interview, United States Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco underscored the point when discussing the geopolitics of disruptive technologies in relation to war in Ukraine. Inverting the usual “What keeps you up at night?” question so often asked of cybersecurity officials, Aspen Digital’s Garrett Graff asked Monaco what’s helping her sleep well these days. She pointed to the “international unity” that was needed to establish an unprecedented sanctions regime to respond to Russia’s aggression. Monaco shared that she draws hope, more broadly, from the growing cooperation between national governments, corporate representatives, and others: “The amount of international cooperation that we have had and the seamlessness with which we work … there isn’t a cyber investigation or disruption that we are involved in that does not have an international component, that, increasingly, thankfully, doesn’t include cooperation by the private sector, and cooperation from the victim. It’s still bumpy, but it’s helping.”

Monaco also discussed the Department of Justice’s increased cooperation with cross-government teams to combat the growing trend of autocracies attempting to project their power beyond their borders, as well as partnerships with the Department of Homeland Security and “a host of about 14 different U.S. attorney’s offices” to address and combat adversaries’ attempts to misuse advanced technologies. Similarly, in the international arena, she described a “galvanizing” of the international community for increased cybersecurity regulation. The increased cooperation she described, and the need for more of it at all levels, was echoed in other panels throughout the three days — particularly in discussions about the regulations of generative AI.

While there’s been some promising international cooperation regarding cybersecurity regulations, there are also emerging areas of conflict, including in regards to social media platforms. In the U.S. and other Western countries, legislators and government officials have grown increasingly concerned about the Chinese-owned platform TikTok. Erich Anderson, general counsel of TikTok’s parent company ByteDance, echoed Baker’s comments about the challenges of operating in different national contexts around the world. He noted that “the internet was designed with global standards in mind,” and for TikTok and similar companies, there is a “big challenge to try to figure out how do you build global systems efficiently in a way that are compelling, while grappling with some of these national security challenges.”

Anderson shared how the company is working to address the data security and privacy concerns of U.S. officials through its Project Texas, which the company says will ensure U.S. users’ data remains in the country. However, without any overarching system to ensure the cybersecurity of users around the world, governments have considered — and begun to enact — restrictions on the platform, including the European Union banning the app from staff devices and the state of Montana’s total ban of the platform. Both the realized and potential bans of TikTok point to a world that needs greater global cooperation for the guaranteed safety and security of users around the world. As Anderson put it, “banning a platform like TikTok is basically a defeat. It’s a statement that we’re not creative enough to figure out a way to work on these things and so we ban, instead of engaging on the problem set and taking a risk-based approach.”

As the challenges of effective policymaking across a host of domains become more complex, it is clear that the need for cross-sector and cross-government cooperation will only become more important — and the pressures related to potential areas of conflict and competition more difficult to overcome.

Civil society is giving autocratic regimes a taste of their own medicine

In a presentation titled “The Autocrat in Your iPhone,” Ronald Deibert, director of the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab, explained how “there’s been a proliferation of firms that are providing products and services to governments to enable them to [spy on their citizens] — various firms that Citizen Lab and others have tracked over the last decade are selling their technologies to governments who are turning around and abusing them.” The abuse can look like large-scale monitoring of entire communities, intercepting information via telecommunication networks, or as Deibert highlighted in his presentation, targeted attacks against individuals to “control dissent, neutralize political opposition, or undermine human rights activists” via spyware installed on their personal devices. Deibert drew upon case studies from victims in the United Arab Emirates, Mexico, and Saudi Arabia to demonstrate the widespread nature of this kind of abuse. In these examples, targets have received unsolicited, personalized text messages that ultimately hijacked the victim’s phone — gaining access to their email, location history, or camera, which, in some cases, has led to the imprisonment or murder of the victims.

Governments engaging in cyber warfare against members of civil society are using technology that is readily available for government use but lacks regulation. “The overarching problem with this industry is that these firms [who are providing spyware tools to governments] justify what they’re doing by saying, ‘Look, our technology is strictly controlled and helps governments investigate serious matters of crime and terrorism,’” Deibert said. “The problem is that in many countries around the world, what counts as a criminal and what counts as a terrorist is very fluid.” And with governments increasingly using these tools beyond their borders, “it’s not just a human rights issue — this proliferation is the Wild West and is a serious national security concern.” Deibert also pointed to the importance of collaboration in combatting this growing challenge, highlighting the creation of the Amnesty International Security Lab, with support from Apple and the Ford Foundation, as a positive development.

During a question and answer session, Deibert shared his hope that government action will help bring more accountability to the space, “President Biden issued this executive order, which basically prohibits the use of commercial spyware that represents a risk to U.S. national security or is involved in human rights violations worldwide.”

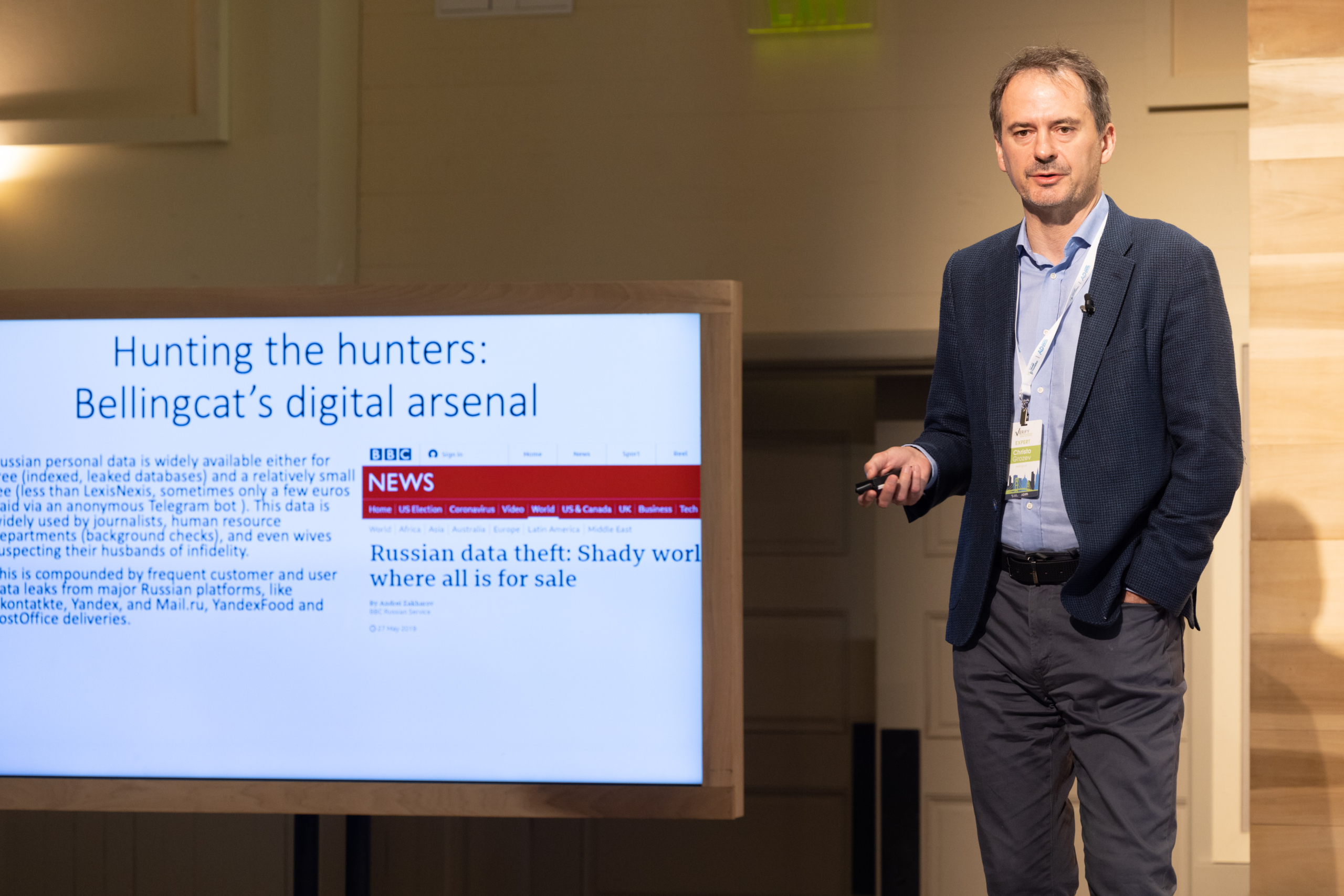

In another presentation, “The Alchemy of Open Source Intelligence,” Christo Grozev, the lead Russia investigator for the journalism organization Bellingcat, shared more about how his team uses open-source information to fact check and shed light on geopolitical matters. Since the war in Ukraine started, Grozev and his team have been focused on Russian operations, using facial recognition tools, leaked datasets of hotel stays and flights, and passport numbers to identify Russian operatives and to disprove the misinformation shared by the Russian government.

Grozev shared several case studies from Bellingcat’s work, describing how they use sources as diverse as flight manifests and personal social media profiles to conduct their research. He also explained the rules he holds for himself before beginning an investigation: “There has to be a hypothesis that a government crime has been perpetrated and you have to be able to achieve that conviction through open source only.” Grozev and the team at Bellingcat focus on government crime specifically because, “in today’s world, it is very hard to prosecute by traditional law enforcement.”

The rise of AI brings big challenges — for cybersecurity and for society

There’s been a growing interest in large language model technology like ChatGPT, and as these tools have become more available to the general public, there’s been increased scrutiny of how they work and their very real drawbacks and limitations. This was a topic that spanned several conversations at Verify — while AI’s potential benefits are vast, from increased efficiency in completing tasks and research to quickly generated responses on complicated topics, the potential challenges are equally clear, particularly as AI enters new domains.

During a live taping of the Lawfare podcast, cybersecurity expert Nicole Perlroth pointed out how AI is a double-edged sword when it comes to cybersecurity: “AI will be dual-use technology. Just as you can use it for penetration testing or finding vulnerabilities in a system to patch, you can also use that knowledge to exploit those vulnerabilities to get inside.” Perlroth pointed to examples of bad actors using the tool to learn how mass shootings or the 2021 SolarWinds supply chain hack were planned. Perlroth cautioned that when working with something that has so many capabilities, it’s best to tread carefully: “Speed is the natural enemy of security and we haven’t figured out how to do cybersecurity 1.0, let alone how to do this with AI. … I really think this is a moment where we have to move very slowly.”

This apprehension and need for caution were echoed by others. Alex Stamos, of the Stanford Internet Observatory, spoke about needing to reframe the way that society, as a whole, thinks about AI: “The problem here is not that it’s too smart, it’s that we assume that it’s smart. We assume and we anthropomorphize it because we naturally assume that something that can do that is living, it has a soul, beliefs, and internal thought. It doesn’t have that. It’s a statistical model, just a graphics card.”

Responding to these concerns, the value of collaboration was underscored by Dave Willner, former head of trust and safety at OpenAI. Willner highlighted the reinforcement learning process that OpenAI has in place and the interest they have in getting public input on these matters. “It’s not one [person] deciding the model weight [the strength of the connections large language models assign to the individual nodes in its data set]. The initial model weights are a product of all the data that goes into it. … And we then influence those model weights further through a reinforcement learning process. That’s something that my team helps us figure out, because we have to make a bunch of decisions. But more broadly, we do want there to be a social conversation about what the limits should be on what these systems can and can’t do — we think that would be a good and healthy conversation.”

The AI field is still rapidly emerging, and as emphasized throughout the conference, without any set of regulation or content moderation, AI has presented and will continue to create challenges both for cybersecurity and society at large. Over the course of Verify, issues of trust and safety and content moderation frequently came up in response to making AI more effective and safer for its users. Vilas Dhar, president of the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, underscored the importance of a society-wide conversation about how these tools are deployed, and the rules that govern their use: “Whether it’s the press that’s sharing public discourse or it’s scientists and researchers coming together to actually talk about it, the fact that values need to drive outcomes is, I think, just clearly obvious. We have to figure out how to get it to work. We have to do it really fast.”

Amidst the wide range of topics that were covered at this year’s Verify event — everything from generative AI, targeted ransomware, and open-source intelligence to social media platforms and growing great power conflict around the world — it remained clear that there’s a larger conversation happening about the role and direction that technology has on our society. These fields are developing so rapidly that policymakers will always struggle to keep up, but as they continue to develop, users’ safety and security needs to be kept front and center. As Jim Baker put it, “values drive policies and policies drive decisions,” and the collective, collaborative work to create frameworks that prioritize the ethical use of technology for humanity’s benefit must remain of paramount concern.