There were no all-male panels at the Open Government Partnership Summit in Tbilisi, Georgia last month. There were three panels on gender and a full-day on feminist open government. These are baby steps toward the aspiration of Feminist Open Government that the government of Canada, which now co-chairs the Open Government Partnership, is promoting. But they aren’t nearly enough to fulfill the promise that all government decisions are visible and accountable to all citizens—men and women.

Feminist open government is what open government should be: transparent and accountable to all its citizens. It considers the specific needs of women and girls, examines—and dedicates resources to understanding—how policies affect men and women differently, and ensures women can access information and feel safe demanding accountability from their government.

There are many reasons why a Feminist Open Government is a good idea: women constitute half of the world’s citizens, but are systematically discriminated against. Women are more likely to use public services, and be disproportionately affected by tax decisions, both prevalent themes in the partnership’s commitments. In addition, women are more likely to be employed in the public sector. Simply put, if we don’t have a feminist approach to open government, we are not engaging half of the citizens and decision makers who are supposed to be a part of it.

When we review proposals at the Hewlett Foundation, we often ask the question “what does success look like?” hoping to help our partners (and ourselves) think ambitiously and concretely about outcomes and indicators. We also encourage grantees to think about “tripwires” or what would tell us that things are off-track. I worry that I spotted some common tripwires at the Open Government Partnership Summit.

Here’s how we won’t make open government more inclusive, responsive, and accountable to women:

- Toolkits. Checklists, guidelines, and other standardized materials—are never enough to induce real change. At the Hewlett Foundation, we have seen many toolkits and other tools rolled out under the assumption “if we build it, they will come.” It simply does not work. Gender mainstreaming, or applying a gender lens to any topic, requires doing so throughout the entire process. Feminist open government will fail if it’s reduced to one set of issues (like “development”) and a toolkit on “how to do feminist open government” is seen as the answer.

- Obsessing over specific gender commitments. Commitments are a tangible and observable way to confirm whether the Open Government Partnership benefits women and girls across the world. But a handful of gender-specific commitments run the risk of standing separate and apart from other government priorities and being neglected or failing. True feminist open government would have a gender lens applied to every issue the Open Government Partnership focuses on—whether it’s infrastructure, natural resources, anti-corruption, health, or nutrition. No public policy is gender neutral.

- Not paying for it. There’s no free lunch. A common reason these kinds of efforts have failed in the past is that there are insufficient or no budgets behind these commitments. This applies to both countries who have committed to National Action Plans as well as funders who support the Open Government Partnership. Good intentions can remain just that without resources to support organizations to be a part of the National Action Plan process, including bilateral funding to help build government capacity around this issue.

But here’s one way the Open Government Partnership, governments in Canada or Ghana, and funders can help: include women’s rights and advocacy groups from the beginning. The staff and members of these organizations know these issues better than anyone, and have worked on them in the communities they live in with local and national government officials, and at the global level. They also understand the politics of the issue, and as women in advocacy processes (i.e. the obstacles that women face in advocacy because they are women), both are a central part of the Open Government Partnership process.

Here’s what can happen if the partnership incorporates women’s rights and grassroots advocacy groups at the start, and in their consultations and drafting of National Action Plans:

- Legitimacy and insights across all policy issues. Countries will have more solid, legitimate commitments to improve women’s lives that extend to all government commitments (not just “gender commitments”). They can also articulate how the Open Government Partnership can improve women’s rights and their own policy and advocacy efforts.

- Make the case for other civil society groups to participate. Feminist organizations can help explain why other civil society groups should participate in the Open Government Partnership and how it can advance women’s rights and other policy and advocacy efforts.

- Build bridges between open government experts and women’s rights policy and advocacy leaders. Governments and the partnership can learn how to better include a gender perspective, the differentiated effect policies can have on women and men; why they should invest in data disaggregated by gender, and build in gender indicators. Feminist organizations, on the other hand, can learn more about how to use open government tools, including how to provide access to information requests, use open data, and track government budgets. This could be a potential area for the Open Government Partnership’s Multi-Donor Trust Fund and bilaterals.

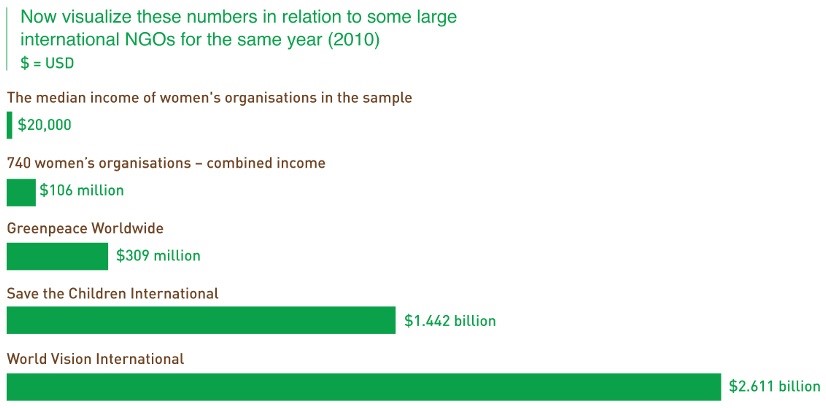

But funders like us have a role to play—and should be playing a bigger role. Women’s rights organizations tend to be underfunded and overstretched. In a 2013 Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID) report, authors Angelika Arutyunova and Cindy Clark found that the average income of 740 women’s organizations surveyed was $20,000 a year. An OECD review of financial support given by major donor countries found that just 0.5 percent of the billions of dollars allocated to promote gender equality in poorer countries in 2014 was reported as going to women’s rights organizations (the figure was down from 1.2 percent in 2011).

For women’s rights organizations to participate in the Open Government Partnership process, it will take time and resources they don’t have right now. This is especially true for grassroots organizations that may not be located in the capitals where a lot of the consultation processes take place, including the Open Government Partnership Summit and the National Action Plan consultations.

At Hewlett, we have supported feminist organizations in Mexico that are using transparency and accountability tools to further their advocacy strategies, like the Instituto de Liderazgo Simone de Beauvoir or Equis Justicia para las Mujeres. Globally, we support a cohort of grantees who are exploring the intersection of gender in the extractives sector, like Publish What You Pay and Oxfam. All of these organizations have valuable lessons that can be leveraged in feminist open government and in the Open Government Partnership’s own process of thinking about inclusion. Transparency and accountability tools have been very helpful to feminist organizations to further their advocacy strategies. But they have also documented the obstacles and challenges that women face in accessing information or demanding accountability from their governments because they are women (in addition to being young, and/or indigenous). On the other hand, more traditional transparency organizations are finding that doing gender work is complicated, long-term, and requires building capacities. And we’re looking for ways we can strengthen and amplify our support.

I remain excited about the potential for Feminist Open Government commitments at the Open Government Partnership and beyond to help all citizens—men and women—see and shape how their governments design and deliver public services like health care and education. But we all have more to do.

What do you think will help governments be more accountable to all of their citizens? What should champions of feminist open government avoid? Send me an email, or in the spirit of transparency, tell us on Twitter @alfonp.