What do you believe the arts sector ought to look like twenty years from now? This is a question that every arts funder should be able to answer with a healthy amount of specificity. Whether arts funders choose to acknowledge it or not, much of what we do shapes the future of the field. This point is not intended to give arts funders more power than we actually have but to acknowledge reality. Funders’ actions — including when we choose not to act — prioritize, privilege, and capitalize particular models over others. This is why the funding community must grapple with the ways that arts leadership is changing and, with clear eyes, recognize the role that we are playing in shaping the future of the sector.

My own answers to these important questions are informed by research commissioned by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s Performing Arts Program and conducted by Open Mind Consulting, which we describe in Moving Arts Leadership Forward. Among the critical findings in the report is the importance of generational change in understanding what is happening in the arts organizations we support. Since we published the report, I have had conversations with colleagues from both funder and nonprofit organizations of all sizes, and one thing is clear: The topic is fraught. Individuals often reject the generational labels that demographers have assigned them, and resent the generalizations made about their cohort. And yet, refusing to appreciate generational differences and their impact on virtually every aspect of our work only delays our ability to acquire the skills that are necessary to manage this impact — which is why I want to start with it here.

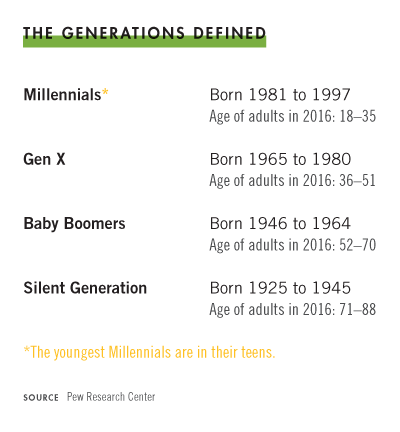

Today’s workforce is largely made up of three generations spanning more than fifty years of experience — older Millennials, Generation Xers, and Baby Boomers. Multigenerational workforces are not new, of course, but what is different today is that the three generations are represented in relatively equal proportion. In California, for example, the workforce in 2015 was 35 percent Millennial, 36 percent Generation X, 27 percent Baby Boomer, and 2 percent Silent Generation. This is very different from the sector’s recent history, when Baby Boomers comprised more than 40 percent of the workforce and played a primary role in shaping the sector. It was the Boomers that predominately led the cultural surge of 1960s and 1970s, which significantly diversified and expanded the field and established the nonprofit arts sector as we know it today.

We are in the midst of a generational sea change, which we can expect to last until at least 2034, when the youngest Baby Boomers will turn seventy. This shift, which is palpable within the sector, corresponds with larger societal changes. Though generational categories are just one dimension of our experiences and are laden with stereotypes that are reductive by nature, they can still shed light on the very different expectations that individuals bring to the workplace and their careers — even when they share a common commitment to the arts.

We are in the midst of a generational sea change, which we can expect to last until at least 2034, when the youngest Baby Boomers will turn seventy. This shift, which is palpable within the sector, corresponds with larger societal changes. Though generational categories are just one dimension of our experiences and are laden with stereotypes that are reductive by nature, they can still shed light on the very different expectations that individuals bring to the workplace and their careers — even when they share a common commitment to the arts.

The structures and cultures of the sector’s arts organizations reflect the perspectives most associated with the generations that established these organizations, namely, the Silent Generation and the Baby Boomers. Broadly speaking, those perspectives include a tendency toward hard work and long hours, valuing independence, and appreciating the clarity and efficiency that comes with organizational hierarchy.

As Millennials and Generation Xers make up a larger proportion of the workforce, there is increasing pressure on arts organizations to include their perspectives. Those that identify with Generation X tend to value skills over long hours, want to strike a balance between personal and work time, and prioritize meaningful work ahead of career advancement. The work environments that Generation X favors are informal and flexible and provide fluid access to leadership and information. The Millennial work ethic is also inclined to question the notion of long work days and seeks to balance work and personal time with community involvement and personal development. Millennials tend to have a very collaborative and entrepreneurial approach to work. They also lean toward organizational structures that are highly networked and goal oriented and embrace technology and innovation.

These four generations even differ in their understanding of the term leadership itself. People who identify with the Silent Generation tend to equate leadership with seniority or something that accompanies formal status. Baby Boomers see leadership as based in experience, meaning that leadership is accrued largely through the act of doing. Those that identify with Generation X tend to view leadership as based in merit — in their eyes, leadership is earned. Millennials, who grew up in a much more networked society, see leadership as conferred by participation. These differences mean that multiple generations are working shoulder to shoulder but lack agreement on fundamental workplace values. This contributes to tension and misunderstanding that flow in both directions. Younger generations, for example, can feel frustrated by a perceived lack of innovation, while older generations presume that younger individuals often want to innovate just for the sake of innovation.

We are in the midst of a shift from a culture that favors clear lines of authority and hierarchy to one that prefers flatter, highly networked, and nonlinear systems and approaches. We are in a period where positional status, hard-fought experience, and acquired wisdom is being rebalanced against calls for open access to information and opportunities, and an ethos in which the voices of all carry equal weight, regardless of position or experience. In a workshop that I facilitated with the multigenerational staff of a large arts organization, I cited this quote from a Deloitte University report, spoken by a twenty-nine-year old manager, that illustrates how Millennials conceptualize leadership: “all points of view on this team carry the same weight. People have the freedom to express themselves whether they have thirty minutes or thirty years of experience.” The response of one late-career leader in the room was emphatic: “I want to know: Where is the wisdom in all this?” This is an example of the nonprofit arts sector grappling with how to accommodate a new set of generational perspectives. It is not helpful to resist these perspectives in this time of change. While the categories can be flawed, the varied perspectives that each generation holds is exactly what the arts sector needs to address two of its most pressing problems: unrealized talent potential and constrained adaptability and relevance.

Unrealized talent potential

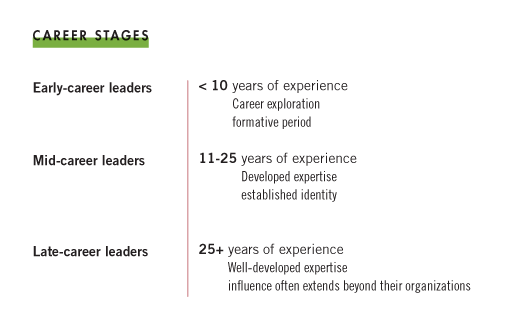

Our research shows that along all points of the career-stage spectrum, nonprofit leaders are struggling to reach their fullest potential. Executive directors feel enormously burdened, senior staff feel simultaneously overstretched and underutilized on questions that matter most to their organizations and the field, and younger professionals feel undervalued.

Many late-career leaders — those with twenty-five or more years of experience — are electing or needing to work beyond the traditional retirement age. A survey of nonprofit leaders age fifty-five and older showed that 60 percent expect to remain in the paid workforce at least until the age of seventy, and 8 percent said they did not expect to ever stop working for pay. In addition to the unexpectedly high level of delayed retirements, the way late-career leaders are “completing” their careers looks very different than previous generations. Many are seeking capstone projects or positions and want to work in ways “where they are less in charge and have more flexibility and less responsibility.” They want to continue working because they are deeply committed to their field and have a strong desire to continue being useful to it, as opposed to sticking around to share their wisdom with others, according to research by Marion Godfrey and Barry Hessenius. While many late-career leaders remain active, it is clear that many are not contributing in the ways that they desire or that best utilize their knowledge and experience.

At the same time, today’s early- and mid-career leaders possess both higher levels of education and more student debt than their predecessors. This leads to elevated expectations for positions with real influence, rapid career advancement, and corresponding salary requirements — expectations that an undercapitalized and crowded nonprofit sector often cannot meet. Our report highlights these findings, as well as an emerging pattern of promising talent moving to adjacent sectors, including into roles as independent practitioners, where they can better attend to their personal needs and professional aspirations. What is more, many executive leaders express a desire to change organizational culture to be more inclusive of different generational expectations but feel they lack models and the support for doing so.

Balanced against this rather bleak picture is strong evidence that younger arts leaders prefer to lead alongside others, and that intergenerational exchange is shown to help people acquire a deeper appreciation for different generational values and approaches to leadership. Similarly, solutions to the career development needs of one cohort can be mutually reinforcing of others. Supporting executive leaders’ desires to move into capstone roles, for example, could help bolster the roles of younger leaders who feel underutilized, which assists in retaining them. The challenge is to move away from historic patterns that favor heroic leadership and to address the needs of singular leaders or groups of leaders (e.g., executive directors or emerging leaders) to develop models that attend to the interconnected nature of leadership.

Balanced against this rather bleak picture is strong evidence that younger arts leaders prefer to lead alongside others, and that intergenerational exchange is shown to help people acquire a deeper appreciation for different generational values and approaches to leadership. Similarly, solutions to the career development needs of one cohort can be mutually reinforcing of others. Supporting executive leaders’ desires to move into capstone roles, for example, could help bolster the roles of younger leaders who feel underutilized, which assists in retaining them. The challenge is to move away from historic patterns that favor heroic leadership and to address the needs of singular leaders or groups of leaders (e.g., executive directors or emerging leaders) to develop models that attend to the interconnected nature of leadership.

Constrained adaptability and relevance

Every day, arts organizations are expected to know more and do more for more and different people. These are the hallmarks of a world that is changing much more quickly than our organizations. It is no longer feasible for one leader alone to manage and respond to the increasingly complex and changing environment that arts organizations face. Elevating the perspectives, experiences, and visions of the next generation of arts leaders — to operate alongside current frames of thinking — holds particular promise for helping the sector keep pace with a rapidly changing environment.

Promoting emerging generational perspectives is especially important along three dimensions: diversity, innovation, and external leadership. Our research shows that arts leaders of all generations have an appreciation for these values, but how they are interpreted by each successive generation is evolving.

Diversity: Younger leaders, from generations that are increasingly racially and ethnically diverse, are especially conscientious about attending to diversity, both in the workplace and in who the arts reach. Older generations tend to prioritize the merits of representational diversity (what demographic characteristics are present), which, of course, helped fuel the significant diversification of the field from the 1960s through the 1990s. Rising viewpoints on diversity incline toward giving precedence to cognitive diversity (diversity of thought) over representational diversity. Millennials, in particular, are more concerned than their predecessors with bringing forward the multiplicity of thoughts, ideas, and philosophies that all people contribute, trusting that a complex mix of viewpoints — even more than tested experience — can help solve problems.

Innovation: Millennials have a penchant for experimentation and doing things differently. They believe that practices inspired by the technology sector, such as “rapid prototyping” and “failing fast,” can help expand the reach and impact of their organizations. Those that identify with Generation Xers and Baby Boomers also value new ideas but lean toward pursuing well-considered possibilities. Both approaches have the same aim — better results — but the different attitudes and risk tolerances can result in very different ideas about the best path to pursue.

External leadership: Today’s younger arts leaders are concerned with having an impact that extends beyond the walls of a single organization. They understand that it is no longer sufficient for the sector to simply provide distinctive work, attract an audience, and secure financial support — they see an explicit role for the arts in contributing to healthier and more just communities. More than older generations, both Millennials and Generation Xers are likely to set their sights on field-level health, cross-sector impact, and addressing broad social concerns. Perhaps due to their increased racial and ethnic diversity and familiarity with democratizing technological tools, younger generations in particular are eager to develop the field along these lines.

Allowing multiple generational perspectives to flourish is important for influencing not only the art that organizations present but also their internal structures and cultures. To ensure cultural vitality, we must ensure that arts programs, as well as the sector’s infrastructure, are attractive to workers, audiences, and donors alike. Holding too tightly to what any one or two generations believe is best will prevent organizations from fully reflecting the multiplicity of expectations that today’s audiences and donors demand. A strong and adaptable sector is one that understands the principles of its authors and, at the same time, is rooted in the values and perspectives of its successors.

Denying generational perspectives will have profound impacts on what our organizations do and how they operate. An all-too-common example of an organization failing to reflect a multiplicity of perspectives was shared with me by a visionary Millennial arts leader of color. This individual is responsible for creating mutually beneficial relationships between their organization (which produces “classical” works) and low-income communities of color. They have a penchant for working collaboratively and balancing community desires with organizational interests, and they embrace the notion of “external leadership.” Yet despite clear successes in their community-focused efforts, their supervisor told them that they “don’t know how to work in an institution.” This exchange places the burden of needed change squarely on the worker rather than the organization, and fails to acknowledge that this individual’s perspectives are exactly what the organization needs if it is going to know more and do more for more and different people, in other words, if it is to survive and thrive in a diverse and rapidly changing society.

What is needed is a fundamental reimagining of leadership, which is not a call that any arts organization or funder can take lightly. But we cannot ignore the risks of doing nothing. If the sector is unable to fully utilize its greatest asset — its people — both the talent sustaining it and its relevance in our communities are in jeopardy.

A clear understanding of how leadership is operating and how most arts leaders are hungry to work in different ways is the first step to setting the sector on the path to a bright future. This understanding will help ensure that the sector can recruit, assemble, and retain the talent it needs and wants; embody the depth of racial and ethnic inclusion that the next generation of artists and audiences demands; and invigorate its best principles with new ways to create and experience art and culture. It means the funding community needs to understand the role that it plays in shaping the future of the field and to actively work toward the vision of the sector we believe the world needs.

Editor’s note: A version of this essay appeared in the fall 2016 issue of GIA Reader.