New ‘Open Rivers Fund’ to restore waterways, remove aging dams

Justin Clifton

Justin Clifton

Fifty years ago, the United States was at the height of a long era of dam construction. Since the first days of the United States, Americans have been building dams and putting rivers to work for mills, to generate electricity and to store water for cities, farms and towns. Dams were considered a symbol of American progress.

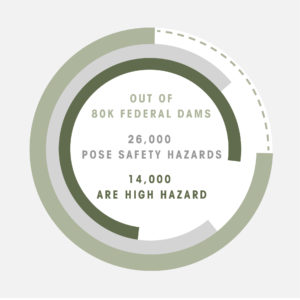

Today, that’s no longer the case. Many U.S. dams are aging, obsolete and causing environmental problems. The most recent report card of America’s infrastructure, issued by the American Society of Civil Engineers, gave U.S. dams a D rating. The Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates that repairing these dams would cost over $57 billion. In the West, dams have altered approximately 70 percent of all rivers, decimating keystone fish like salmon and trout.

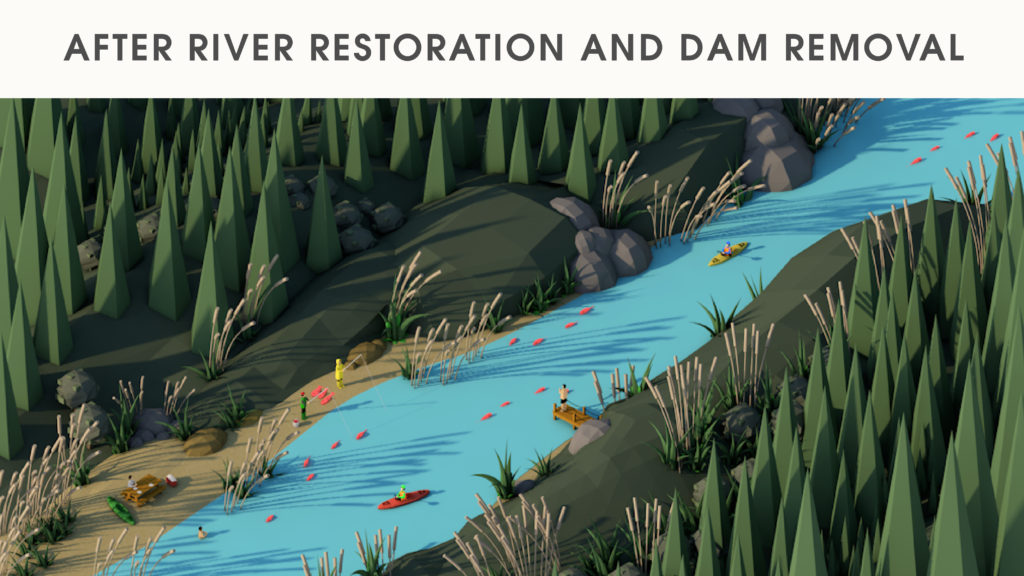

“We have entered into a new era of dam removal because a broad array of people who live in the West ― ranchers, Native Americans, irrigators, businesses, and communities ― are realizing opening up and restoring rivers is an effective way to save taxpayer money, revitalize communities, and help the environment,” said Michael Scott, acting Environment Program director at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, which has been supporting western conservation efforts since it was established.

That’s why, to mark its 50th anniversary, the Hewlett Foundation has awarded a $50 million grant to establish the “Open Rivers Fund,” a 10-year program of Resources Legacy Fund to identify and support community efforts to remove obsolete dams and restore rivers across the West.

“Bill and Flora Hewlett were passionate conservationists who wanted to support local communities and preserve the West’s land and water resources,” said Hewlett Foundation president Larry Kramer. “The Open Rivers Fund honors this legacy by boosting local efforts to remove aged dams that have broad support in the community. The safety, economic, and environmental benefits of removing these dams will be immediate and long-term.”

Kramer described the new effort as “catalytic” in addressing a key hurdle in removing aged dams: funding. “Too often, communities come together and agree to remove an old and obsolete dam only to discover that there is too little money available to do the work. The Open Rivers Fund will provide communities with financial resources where it is needed most,” Kramer said.

RLF, a conservation nonprofit with significant experience in developing and implementing complex conservation programs and projects, has developed a systematic approach to identifying, assessing and effectively pursuing collaborative project opportunities. During the next 10 years, RLF will identify potential dam removal projects—based on the local need, widespread community support and collaboration, and opportunity for multiple community and environmental benefits—and support the work of local groups and agencies in removing the dams.

The Open Rivers Fund will kick off the new program with three projects where economic and environmental benefits have led to broad community support: the Matilija Dam in Ventura, California; a series of dams and obstructions in Oregon’s Rogue River basin; and the Nelson Dam in Yakima, River watershed in Washington.

In southern California, a surfing town embraces its river

“We were always a great beach town,” said Matilija Coalition founder Paul Jenkin. “But the community had all but forgotten the river.” In the early 1990s, Ventura’s beachfront was beset with what Jenkin considers “pretty dramatic beach erosion.” Since then, the city of Ventura has implemented a first-of-its-kind project to manage the erosion and the shoreline. But to really solve the long-term problem, the community had to look inland.

Standing on the restored dunes at Surfer’s Point in Ventura, Jenkin pointed to where the Ventura River estuary meets the ocean. An ocean engineer by training, he explained that the ocean alone is not responsible for the erosion. Also undermining the beach is a lack of river sediment. And preventing beach-enriching sediment from reaching the beach is the Matilija Dam nearly 16 miles upstream of the ocean.

Built in 1947, the dam has been trapping sediment for nearly 60 years. Its 7,000 acre-foot reservoir is expected to be completely filled with silt by 2020. Originally designed to supply water to the Ojai Valley, the dam has been problematic from day one. Its cracking concrete reveals structural concerns that necessitated a major project to lower the height of the dam back in 1965. Now obsolete, a plan is finally in place to engineer its removal. Support from the Open Rivers Fund will help make the project a reality.

“I got involved with the Surfrider Foundation in 1994,” said Jenkin, explaining that the Matilija campaign began by connecting the beach and the dam. “That’s when we printed our bumper sticker that said, ‘Give a Dam. Free the Sand. Grow the Beach.’”

This began to galvanize the coastal community’s support for removing the dam, and Jenkin and Surfrider quickly became key players in the dam removal effort. The dam removal effort gained momentum in 2000 with formation of the Matilija Coalition, which included the outdoor clothing company Patagonia and the anglers’ conservation group California Trout.

These river advocates, along with biologists, brought attention to the fact that in addition to blocking sediment vital to Ventura’s beaches, the dam also blocks passage of now endangered Southern steelhead. The dam and stagnant reservoir harms the health of the entire Ventura River watershed. Dams like the Matilija, other water diversions and developments have so degraded and cut off California steelhead habitat that these fish have declined about 90 percent since the 1950s.

“Restoring unimpeded access between the ocean and coldwater habitat in the headwaters of the Ventura River watershed is essential to saving these fish,” said biologist Matt Stoecker, who produced the documentary DamNation to illustrate how dam removal benefits ecosystems.

“Everybody understands that the dam is obsolete and its time has come,” Jenkin said. “We’re trying to develop a model sustainable watershed. And the dam is the lynchpin to the whole system.”

“Getting kids outdoors and introducing them to natural and cultural resources is part of this reconnection,” said Julie Tumamait, a leader of the Barbareño-Ventureño Band of Chumash, who have lived in the Ojai Valley region for thousands of years. “We grew up with steelhead, trout, deer, rabbit, clams, acorns, walnuts, and wild cherries,” she said.

Removing the Matiljia Dam and restoring habitats submerged by the reservoir will help restore riparian and oak woodlands – essential to ensuring that these wild foods continue to be part of Chumash family traditions.

In March 2016, after more than a decade and a half of study and debate, the community’s many stakeholders agreed on a plan to remove the dam. The project includes several components that will benefit the community through new bridges, levees, and water supplies. It will also enhance the community’s recreational opportunities with the completion of the Ventura River Parkway project, and by naturally restoring the ocean beaches at the mouth of the river. “That’s important,” said Jenkin, an avid surfer and mountain biker, “because that’s how we experience the world around us.”

Interest in Ventura River restoration is also high because “right now, people are interested in the kinds of things we can do to conserve and enhance our water resources,” said Jenkin. “They understand that river restoration is more than just removing a dam.”

Restoring fish and tribal rights in coastal Oregon

The Rogue River flows from the Cascade Mountains through forested canyons and pastoral valleys to the Pacific Ocean on the southern Oregon coast. The Rogue and its tributaries were prime fishing grounds for the region’s Native Americans, including the Umpqua Tribe of Indians Cow Creek Band, who’ve lived here for millennia. In the mid-19th century, however, the tribes ceded their land to the U.S. government. The treaty maintained the tribe’s right to fish throughout their ancestral territory. But the development that followed – dams and water diversions for farms, towns and cities – took a heavy toll on Rogue River fish.

Historically, the Rogue was home to some of the largest wild fish populations of any Oregon coastal river. But its Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead, trout, and other native fish, have declined precipitously – a signal of trouble for health of the entire watershed. To turn this tide, the tribe is working with local community groups, environmental advocates, biologists and natural resource managers to restore the Rogue and its iconic fish. Central to these efforts is removing dams blocking fish passage.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is restore fish populations so the tribe can try to restore its fishery rights on the Rogue,” explained Jason Robison, the Cow Creek Band’s natural resource director. Without enough fish to catch, those rights can’t be exercised.

The past decade has seen major steps forward. Since 2008, three major fish obstacles have been removed: Gold Hill Dam and Gold Ray Dam on the Rogue River’s main stem and Savage Rapids Dam on Bear Creek, a tributary. Consequently, the river now flows freely for more than 150 miles and fish are populating stretches of river from which they’d been absent for decades.

But more work is needed to reconnect fish with cool headwater streams essential to their long-term survival. This is increasingly important as climate change brings higher temperatures. These temperature spikes and drought have warmed Oregon rivers – including the Rogue –so severely that they have killed fish.

The remaining physical obstacles on the Rogue create further problems. “We know that when those species need to move high up into the tributaries to their spawning grounds, they still have to run a gauntlet of diversions in the smaller streams,” said Brian Barr, Rogue River Watershed Council executive director.

One such impediment is the Beeson-Robison Diversion dam on Wagner Creek that diverts water into an irrigation ditch during the spring and summer. “It’s among the several streams that carry the most snowmelt and stay the coldest during the summer. That’s very important to steelhead and coho,” Barr explained.

The Beeson-Robison was first installed in the late 1880s and serves 19 local irrigators. While only 5.5 feet high, the dam blocks fish passage so the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has identified it as a priority for removal. Because this can be accomplished relatively quickly, the project has risen to the top of the to-do list. With support from the Open Rivers Fund, it can get started in the summer of 2017.

The project will replace the dam with what’s called a “roughened channel,” a kind of in-river ramp. While continuing to supply irrigation water it will enable salmon and steelhead to reach vitally important habitat. Like most river restoration projects, it’s a collaborative effort, involving multiple community organizations, state and federal agencies, and local landowners.

The property owners who use the irrigation water all support the project. Bob Hackett’s family raises its own food and uses this water on their vegetables, orchards and hay fields. A river enthusiast, Hackett looks forward to the win-win of the project – improved conditions for fish and continued irrigation water access. “I wouldn’t anticipate any usage changes as a result of upgrading the structure,” Hackett said.

“In restoration, probably the biggest bang for the buck is to restore connectivity,” said Scott Wright, an engineer and principal with River Design Group, an Oregon-based consulting firm specializing in river restoration. “When I was growing up in the Rogue basin, I was watching significant dams being built. Now my kids, who go down to the Rogue with me, see the opposite,” he said.

“Within one month after the Gold Ray dam came down, we saw fish passing through. With the Gold Hill dam removal, we saw fish passing through the opening the very next day,” Wright recalls. “People come from all over for steelhead and salmon fishing, and guides are telling us that fishing is some of the best it’s ever been where Gold Ray was taken out. Raft guides say their most popular trip is now one they couldn’t take before the dams came out.”

These recreational opportunities are important to the local economy and help rally community support for Rogue River restoration. That these projects support the tribe’s economic and social goals is also key. “Diversion dams are a thing of the past. From a tribal perspective any way we can increase fish production, water quality and quantity is huge,” Robison said. “Having the tribe involved is crucial. The tribe has been here forever and we’re going to be here forever.”

A Washington community tackles flooding problems

The Yakima River flows through central Washington’s dry, sagebrush highlands into the Columbia River at the Oregon border. Here, rivers are the lifeblood of their communities, including for the Yakama Nation tribes who’ve lived here for centuries. This is now an important agricultural region and the Yakima has been diverted and dammed to deliver water to farms, homes and cities. One of these dams is the 8-foot high Nelson Dam, on the Naches River just upstream of the city of Yakima.

The Naches is the Yakima’s largest tributary. Its health is vital to the region’s salmon and steelhead. But Nelson Dam, first built in the 1920s to divert water for Yakima residents’ yards and gardens, creates serious problems. Its existing fish passage doesn’t work as it should. Sediment has built up behind the dam, creating flood hazards and degrading fish habitat. Now, as part of countywide plans to restore the Yakima, plans are in place to reengineer the dam so it can provide irrigation water while letting fish and sediment pass. Support from the Open Rivers Fund will help make this happen.

“The old infrastructure doesn’t work very well,” said Steve Malloch, a hydrologist and lawyer who’s worked extensively on river restoration and water policy. The dam’s created a sediment buildup that causes the river to overflow in times of very high water.

“We’ve had some severe floods in the past decade and have been spending more and more money on repairs,” explained Yakama Nation fisheries research manager Dave Fast.

“When big rains fall, particularly when there’s snow on the ground – warm, heavy rain on snow, the river floods,” Malloch said. “It’s happened several times in the last 20 years, so it’s not a rare event.” When these floods occur, “they sweep across and close Highway 12,” blocking emergency services, including access to the local hospital. “Each time this happens, the county has had to spend more money on levee repair than the Nelson Dam removal and replacement will cost,” he said. So removing the existing dam will solve a public safety problem for community businesses and residents – and save money.

It will also help restore the river’s native fish. Dams on the Yakima and tributaries have degraded river habitat severely, decimating the river’s native fish. The watershed’s wild sockeye, coho and summer Chinook have been extirpated but reintroduced. Only small populations of spring and fall Chinook, steelhead and bull trout remain.

Restoring the river’s native fish is vitally important to the Yakama Nation, said Phil Rigdon, Yakama Nation deputy director of natural resources. “Salmon are fundamental to our culture – to who we are as a people. It’s our responsibility to make sure they’re taken care of for the long term, to respect and honor them, and make sure they’re healthy.”

Salmon are also central to the tribes’ treaty with the United States that guarantees tribal fishing rights. “What good is the treaty right if you don’t have the resource to use,” Rigdon said. “Our tribe is taking a lead role in a lot of the restoration that includes doing work like the Nelson Dam removal. Our goal is to get the fish back to where they once were.”

“Removal of the City of Yakima’s Nelson Dam and replacing it with a roughened channel will address an important safety concern for our community,” said David Brown, City of Yakima Water/Irrigation Manager. “When we have opportunities like this one to improve the safety of our community and benefit the environment while saving taxpayer dollars, it just makes sense to pursue.”

While the primary goal of reengineering Nelson Dam is to solve the flooding problem, this solution “has a lot of ecological benefits,” Malloch explained, adding, “Fundamentally, the best way to reengineer the dam is in a way that lets the river be a river.” With the sediment bottleneck removed, the river will be able to use its natural floodplain to accommodate excess water.

“The more we can keep the river in balance, the better off we are,” said Yakima County natural resources specialist Joel Freudenthal. The existing dam will be replaced by a roughened channel that will allow continued irrigation water access, allow fish passage, and reconnect the river with its floodplain. This will open about six to nine miles of river that’s important salmon and steelhead habitat.

Fish passage and habitat restoration are major goals of a watershed-scale conservation strategy known as the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, of which the Nelson Dam removal is one key piece. “We think we can get several hundred thousand salmon back into this basin with the fish passage and habitat work we’re doing,” said Malloch. Project design for reconfiguring Nelson Dam is expected to be finalized next year, with dam removal scheduled for fall 2017.

“We started this process about nine years ago,” says Malloch of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan. “It’s been a remarkable success story,” he said. “The community’s major interest groups – tribes, irrigators and agencies – came together to figure out how to craft a solution that would serve all of their needs. That collaboration made it possible for us to approach individual projects like this one: public safety, irrigation water and fish restoration will all be achieved by reengineering the Nelson Dam.” And there’s a bonus: “Giving the river room to be a river,” said Malloch, “is the only solution that makes economic success.”

Editor’s note: Elizabeth Grossman is an award-winning journalist specializing in environment, science and related policy issues. She has written for Scientific American, National Geographic, Washington Post, Grist and many other publications.