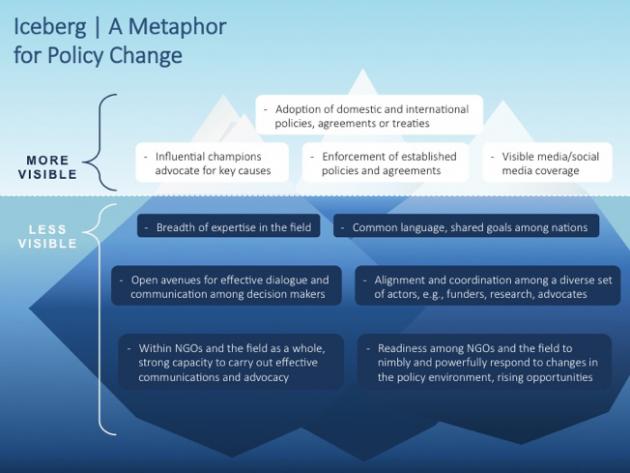

The iceberg metaphor for policy change, as described by Rhonda Schlangen and Jim Coe at BetterEvaluation.org (Image Credit: ORS Impact)

How do you measure the effectiveness of policy work? There may be a single decision-point (or a distinct set) that the work is aimed toward, but focusing only on those points glosses over the hard, necessary effort laying the groundwork for success, which can often take years. What’s more, tracing the causes of a particular win is fraught with uncertainty; how do you disentangle the sometimes multileveled efforts as well as other factors wholly external to them? These challenges were brought home to us as we thought about how to gauge the impact of our recently concluded Nuclear Security Initiative, (NSI), which made roughly $25 million in grants between 2008 and 2014. As we do with much of our work, we have been looking back at our efforts in order to find useful lessons, including by commissioning research firm ORS Impact to conduct a summative evaluation. While a traditional summative evaluation gauges the effectiveness of a social program—which can usually be judged straightforwardly by identifiable and quantifiable results—the relationship between efforts and results in the policy sphere is much murkier.

Policy-related efforts are ultimately about influencing decision makers, yet influence might be achieved by various means (public pressure, media visibility, or advocacy targeted at specific policymakers) and it is hard to anticipate which will work best. Plus, outcomes can sometimes be determined by circumstances beyond grantees’ control. And the time horizon for policy change varies widely depending on the issue and may stretch for many years or even decades. So instead of judging the NSI according to a binary success/failure framework or even a scorecard of policy change “wins,” the evaluators looked for its most significant impact, the areas of meaningful progress on our goals, and also where progress was stalled.

The evaluation has been completed, and it offers useful insights for future work on nuclear security as well as other policy areas. In addition to the report the evaluators prepared for our board, here are my own impressions of the evaluation, and NSI, as a consulting program officer on the effort. In particular, I was impressed with the realism ORS Impact brought to the assessment of policy change work. Their key findings are captured in two conceptual frameworks: 1) a three-legged stool of policy change supported by analysis, advocacy, and coordination, and 2) an iceberg graphic that requires us to look below the waterline to appreciate many of the ways progress is actually achieved.

Analysis, Advocacy, and the Three-Legged Stool

NSI put a special emphasis on the development of the field’s advocacy capacity. The evaluation team was told in interviews that support from funders had previously tilted too heavily towards research. As one interviewee noted, “[to advance policy solutions] you want to have a set of grants that goes at the drivers of policy.” NSI also encouraged grantees to focus on policy relevance in their work. While research and detailed analysis are essential to advancing the discourse, research and analysis alone are unlikely to achieve policy change. And advocacy and communications must be more than a late-stage add-on; these components must be strong and well-integrated from the outset.

This holistic approach can be viewed as a stool supported by the three legs of analysis, advocacy, and coordination. In other words, the different players in the nuclear security field—and other fields, as well—are all vital to achieving progress, and the key is for each to contribute to their common cause according to their comparative strengths and weaknesses. Thought leader or gearhead, polemicist or operative, each has his or her part to play.

Policy Change and the Need to See the Whole Iceberg

Evaluating efforts to affect policy is particularly challenging because impact is a function of so many factors, from the complexities inherent in the decision-making environment to the types, scale, or mixture of strategies being underwritten. The best way to deal with this challenge is to broaden the notion of what is considered a success. Instead of setting sights only on big policy breakthroughs, look for additional forms of progress as well.

Policy change is like an iceberg; by its nature, much of what’s important is hidden below the waterline. Achievement of a significant policy target is merely the highest-profile form of impact rather than being the only meaningful metric for gauging progress. Success in policy change rests on a deep, wide base of related impacts that are much less visible. These types of wins include development of a robust infrastructure to support ongoing work and setting up the enabling conditions for policy change. (In the latter phase of the Initiative, Hewlett joined with other funders to establish N Square, a fund dedicated to supporting innovative approaches and new actors on nuclear security.)

The current debate over the negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program illustrates the point. With the April 2 announcement in Lausanne, Switzerland of a political framework, prospects for an agreed diplomatic solution are looking good (though by no means a sure thing). Beneath the water, though, are the nuclear security community’s vital efforts to give the best chances of success. The diplomacy with Iran has been just as hotly debated as the New START agreement—a key policy win for NSI’s grantees—was, and over a longer stretch of time. Faced with hardline critics trying to undercut the talks by portraying diplomacy as appeasement, grantees have fought hard to protect the policy and political space to give negotiators room to work. Their efforts were also built on a three-legged stool—with broad-brush advocacy about the value of diplomacy, detailed analysis of the specific provisions being negotiated, and close coordination between these two levels.

Clearly there is much to be gained by looking beyond the high-profile policy wins in this type of evaluation. Whether you take as your model the three-legged stool, the iceberg, or both, the key is to try to capture the hidden complexities of policy work. We’re grateful to ORS Impact for helping us see that complexity and hope others learn as much from their work as we have.