Moving as one: Community in the art of Nā Lei Hulu

Weaving together a cultural community while celebrating individuality can be challenging. The artists of Nā Lei Hulu I Ka Wēkiu understand this deeply. For over two decades, the Hewlett Foundation’s Performing Arts Program has funded this company of dancers as part of our efforts to support meaningful artistic experiences for communities in the Bay Area.

Nā Lei Hulu has been celebrated for their unique contemporary style called “hula mua,” or “hula that evolves”. By blending traditional hula movements with modern styles, music, and ideas, the company honors a rich Hawaiian cultural heritage while expressing new ideas that reflect an ever-evolving world. With a history spanning over 40 years in the Bay Area arts community, and multiple accolades to their name, the company has brought together people from all walks of life to discover the beauty, legacy, and possibilities within hula.

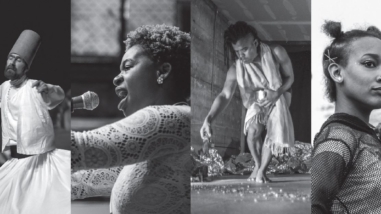

To learn more about the company’s work, we spoke with their founding Artistic Director Patrick Makuakāne and dancers Ryan Fuimaono, Shawna Alapa‘i, and Kate Motoyama about how hula has shaped them as people and creatives — and how, through their artistry, they continue to create new ideas of who they and their community can be.

Early encounters with hula

PATRICK

Born in Honolulu, Patrick Makuakāne grew up during a complicated time in Hawai‘i’s history. “We just became a state a few years prior to my birth, and so everybody was rah, rah, America,” he recalls. “My upbringing was mostly like pseudo-American slash local.” As a result, he felt disconnected from his Hawaiian heritage. Fortunately, initiatives such as the Kamehameha Schools Explorations program offered Native Hawaiians like Patrick the opportunity to learn more about their cultural roots and traditions.

When he was first introduced to hula at school, Patrick didn’t like it. “I recognize now that [it was] because the guy who was teaching it was extremely flamboyant…[H]e scared me with his confidence and his flamboyance… I guess, because as a young child, I knew that I was gay…and it was this sort of weird, internalized phobia like, oh, that’s how I’m gonna be.” It wasn’t until high school, where he was exposed to an all-male dance company that performed at Andrews Amphitheater, that Patrick fell in love with dance: “I was blown away. They seemed super athletic. I thought, ‘Oh, my God!… I want to dance for them.’”

Yet, he was still conscious of how he presented himself: “trying to hold on to that masculinity while being graceful… [I]t’s that sort of balance, kind of like a masculine grace… [that] defined the way I moved as a dancer because I didn’t want to be perceived as gay.”

Patrick MakuakāneI was blown away. They seemed super athletic. I thought, ‘Oh, my God!... I want to dance for them.

KATE

Kate Motoyama’s early resistance to hula stemmed from different sources. As a child, she gravitated toward ballet more than Hawaiian dance. Her father would read books to her at bedtime, and she reflects, “[T]hat influenced me to be a dreamy child with a sense that the world was larger than the Honolulu I was born in.” As a result, she says, “I wanted to be like those books, and hula [and] my Nikkei heritage [were] not represented in those worlds.”

RYAN

Ryan Fuimaono grew up with a Samoan father and a White mother in San Diego. His family expected dance to be a part of his life. “It’s a very Western concept to be like, ‘Oh, only if you like it, or only if you’re good at it’…” Ryan shared, “…that certain people are talented and certain people are not…” His father’s family had a different way of seeing things, “Everybody in the village participates [and] lends their voice to the collective. Whether or not your voice is ‘good’ or ‘bad’.”

Like Patrick, Ryan developed a complex relationship with hula as he neared his teenage years, “[I] was struggling with what’s okay for a boy to do versus what girls should be doing. And also, coming into my own identity as an emerging queer person, very much wanting to fly under the radar and not really wanting to put my creative expression sides out there…”

SHAWNA

For Shawna Alapa‘i, hula was part of an ultimatum. At the age of 11, when she was invited to be the quarterback for the boys flag football team, her grandmother gave her a choice: learn to sew or dance hula. Shawna chose hula, simply because she “thought that sewing was boring.”

Nā Lei Hulu at Burning Man, Black Rock Desert in 2017 (Photo credit: Ron Worobec)

Moving as self-expression

These early experiences impacted how each artist would eventually embrace hula as an art form—as a method of self-expression that is true to them as individuals while maintaining a deep communal connection.

PATRICK

Patrick now approaches teaching with an understanding of gender’s complexity: “I teach both men and women, and [my] approach to both is different…one is not completely 100% masculine, and one is not completely 100% feminine. You have to adopt a range…[I]t’s just a more expressive way of moving…”

He reflects about himself: “[A]fter living in San Francisco for forty years, being gay is something I actually celebrate and often speak candidly to my audiences about…San Francisco gifted me with pride and offered fabulous role models…out and proud gay men making a difference in the world.”

KATE

With time, Kate found herself gravitating back to hula. She began finding a renewed sense of self at Nā Lei Hulu 18 years ago.

“After years of denying the connection of my very soul to the islands, becoming a professor, and speaking perfect English, I longed for a connection to my birth sands,” Kate shares. “Hula invites us to lose ourselves in community to the music and the movement …You can be your authentic self in hula class. It sets you free while moving together in unison and unity.”

RYAN

For Ryan, Hula re-entered his life when he moved to San Francisco in 2007 and joined Nā Lei Hulu. “I achieved a lot of healing,” he reflects, facing the part of himself that had said, “No, cover up! Don’t [let] the world [see] that expressive side of you, or even [your] cultural identity…”

Ryan FuimaonoI achieved a lot of healing…I feel really accomplished [and] really proud to carry this legacy that we come from in Kumu Patrick's line … and wondering what my role will be in the future to create these spaces for community and for others.

He was recently recognized as a kumu, a master hula teacher, which he views as a profound milestone in his journey: “I feel really accomplished [and] really proud to carry this legacy that we come from in Kumu Patrick’s line … and wondering what my role will be in the future to create these spaces for community and for others.”

Ryan has even found lifelong friends through the experience: “I remember coming in as a new person and being a little apprehensive and not knowing where I fit into all of it…but being welcomed in with such warmth and support, and people saying, ‘You’re gonna form relationships here that are gonna last for the rest of your life!’ Fast forward almost 20 years later, and it was so true.”

SHAWNA

Though Shawna initially picked hula due to an ultimatum, on the first day of hula, she experienced something special. “When I saw my Kumu Ellen Castillo dance, I felt in my heart, an awakening and purpose for me in this life and there was no question that I found my place of joy and comfort. Hula was my sanctuary.”

Since then, Shawna has established her own hālau (school/group) in Marin and Sonoma counties. While she is not an official member of Nā Lei Hulu, she and Patrick have a decades-long artistic partnership: “Patrick and I met in 1980, when I began dancing professionally for The Brothers Cazimero. Patrick has featured me in his hula shows as a guest artist in almost every show he’s produced in San Francisco.”

Connecting past and present

Hula is an art steeped in history — helping artists examine where they come from and where they can go. It creates purpose and direction for dancers, as it represents the telling and unfolding of history through the power of dance.

Patrick Makuakāne with Hōike (recital) students in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in 2017 (Photo credit: Susan Baranowski)

RYAN

“We’re all there to have a role in this collective,” Ryan explains, “to tell these stories of native Hawaiians of today and of yesterday, and to tell the stories about our ali`i (our ancestral chiefs). The natural environment and also political things [such as] the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom and the Protect Mauna Kea movement.”

SHAWNA

For Shawna, it’s a similar feeling. “Hula allows me to not only tell the stories of my ancestors but also allows me to transport myself to places of old Hawai`i and of Hawai`i today, therefore allowing me to live in those moments and events that the songs tell of.” It’s also a uniquely embodied experience, “Hula was born from nature. The movements, gestures, facial expressions, and physical strength all come together to express the stories being told in the songs and chants.”

There is a particular way that hula transports us across time — there is an echo of those that came before that reverberate through the dancers of today. It is a form that taps into all the senses of an artist.

KATE

To Kate, it’s “poetry and emotion” in motion. “Rarely have I encountered such beauty and its ability to move me in most writings in English,” she says. “Hula embodies thoughts and feelings captured in the mele (songs) and, in going deeper into the layered meanings of the lyrics, you become connected with Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Indigenous Hawaiians) cultural wisdom and their gift of seeing with fresh eyes what loveliness surrounds you.”

Kate MotoyamaRarely have I encountered such beauty and its ability to move me in most writings in English. Hula embodies thoughts and feelings captured in the mele (songs) and, in going deeper into the layered meanings of the lyrics, you become connected with Kānaka ʻŌiwi (Indigenous Hawaiians) cultural wisdom and their gift of seeing with fresh eyes what loveliness surrounds you.

The lessons and legacy of hula

The arts have a great deal to teach us about our values, resilience, and self-perception. When asked to share their learnings from lifetimes of dance, the artists referenced Hawaiian proverbs or “‘ōlelo noʻeau.”

SHAWNA

Shawna finds inspiration in the ancient chant “A Ko‘olau Au,” meaning “I was at Ko‘olau” (a mountain range on O‘ahu).“It recounts a story of the goddess Hiʻiaka, as she journeys through the Ko‘olau mountain range who went through tribulations and how she persevered,” Shawna describes. “Perseverance is what hula has taught me through this ancient chant. And it has given me the strength that I needed to overcome many challenges in my life.”

KATE

Kate reflects, “My mom and dad were forever giving to others, which turns out to be a Hawaiian value, “ʻōpū aliʻi”, to give freely without expectation of return…That was a value expected of the chiefs of Hawaiʻi. The conversation you begin with a stranger… being there for a friend through hard times, are small examples of this kind of sharing.”

RYAN

For Ryan, the Hawaiian proverb “Not all learning comes from one place,” resonates deeply with his experience in the Nā Lei Hulu community. “Kumu Patrick is one of…a handful of Native Hawaiians who invited me into hula,” he shares. “[They] have seen something in me. And saw that I had gifts worthy to cultivate, and that I had a role.”

The form has taught him to find learning in all experiences: “whether it’s positive, negative, or neutral, there’s something to learn from that experience or from that person that gets put in your path.”

PATRICK

Patrick’s guiding principle speaks to the power of community: “One of my favorite Hawaiian proverbs is, ‘No task is too great when done together by all.’ We have been proving that for decades. You’re strongest in a community. If you’re not treating your community well, then, you won’t have a successful community…and you won’t survive either.”

Shawna Alapa‘iPerseverance is what hula has taught me through this ancient chant. And it has given me the strength that I needed to overcome many challenges in my life.

Nā Lei Hulu in the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco in 2018 for I MUA: Hula in Unusual Place (Photo credit: Patrick Kelly)

Moving forward together

Patrick reflects upon the legacy and impact of Nā Lei Hulu: “How grateful am I? [Sometimes] I think I live my life going from one amazing, blessed event to another…The richness that I’m treated to because of being in this culture and in this dance form, in this art form and living in San Francisco and going back to Hawai‘i. It’s just been such a fulfilling life.”

He will celebrate his 64th birthday in August, and looking forward, he hopes to inspire the next generation of dancers. “So many of us who were with the company in the early days, we’re getting older,” he says. He also recognizes that this work will bring communal evolution: “Now we really have to look to the new generation to let them continue.”

Patrick understands the real-life obligations and challenges of today’s dancers, and he knows these will be crucial parts of the ongoing legacy and longevity of Nā Lei Hulu. He remains an energetic leader, drawing inspiration from the people around him: “I am a firm believer [that] you are what you say. So, if you’re saying I can’t do it anymore, then there you go. But if you say you know what, I’m gonna make something happen…I still have good people around here. I’m excited at what’s gonna happen.”

Nā Lei Hulu’s dancers demonstrate that art can preserve tradition while embracing change, creating space for both collective connection and personal truth. As one era transitions to the next, they continue to teach us that the most powerful movements can happen when communities move as one.

Patrick MakuakāneI am a firm believer [that] you are what you say. So, if you're saying I can't do it anymore, then there you go. But if you say you know what, I'm gonna make something happen…I still have good people around here. I'm excited at what's gonna happen.