Last week, I learned a great deal about lobsters. At a conference. During the process, I learned not just about lobsters and conferences, but about how we can and must do a better job of teaching our children.

Learning about lobsters at High Tech High.

Let me explain: the conference was (full disclosure) funded by our education program in collaboration with the Raikes Foundation, and it was organized by one of our grantees, a public charter school in San Diego called High Tech High. It brought together teachers, administrators, and students from around the U.S. and elsewhere to exchange ideas about “deeper learning”—which is an entirely different way to educate our kids. Rather than list the various characteristics of deeper learning, let me explain how I spent my day at this deeper learning conference, in a session devoted almost entirely to learning about lobsters, and why that was a great thing. Then you’ll know what deeper learning is and why it’s so important that every child receives this kind of education.

The session, which lasted seven hours (yes, you read that right), took place in a classroom at High Tech High. There were thirty or so participants in the session, called A Deep Dive into the World of Lobsters. Other sessions included, among many others, Parkitecture: Using Design and Technology to Support Deeper Learning, and Thinking BIG With Kids Who Are Small: A Deep Dive into Engineering and Literacy for All Ages. Our session was led by Ron Berger and Steven Levy of Expeditionary Learning, an organizationthat partners with public district and charter schools across the country. Seven hours may seem like a rather long time for a conference session. In fact, I have been in many one-hour conference sessions that felt like seven, but this session flew by.

The chairs in the room were arranged in groups of five or six. We were invited over to a tank of lobsters, and asked to get with our partners and select a live lobster, which we placed in a small plastic container filled with cold water on our desk.

Ron then asked the group to conduct a set of scientific measurements. We had to measure the length and width of the lobster’s crusher and cutter claws, measure the length of the carapace, and then weigh the creature. Unsurprisingly, this raised a bunch of questions. What’s a carapace? Which claw is the crusher and which is the cutter? To what decimal place should we record the weight? Should we use ounces or grams? Millimeters or centimeters? And so on. Some of the answers were found in the set of materials we received; others required agreement among the entire class. Agreement was necessary, though, if we were going to be able to compare our data with other groups.

After a certain amount of negotiating, once we agreed on our standards, we recorded our measurements and added them to a large sheet of paper at the front of the class. With the data from all seven lobsters collected and shared, we were then asked to analyze one pair of data.

Our group chose to see if there was a correlation between the width of the two claws. We also found out that lobsters can be lefties or righties—some lobsters’ crushers are on the left, but most are on the right. We then graphed our results on large posters. Ron pointed out how often students working together in the classroom come up with questions that even the experts miss. Even better, these classes are occasionally even tasked with conducting some of the research!

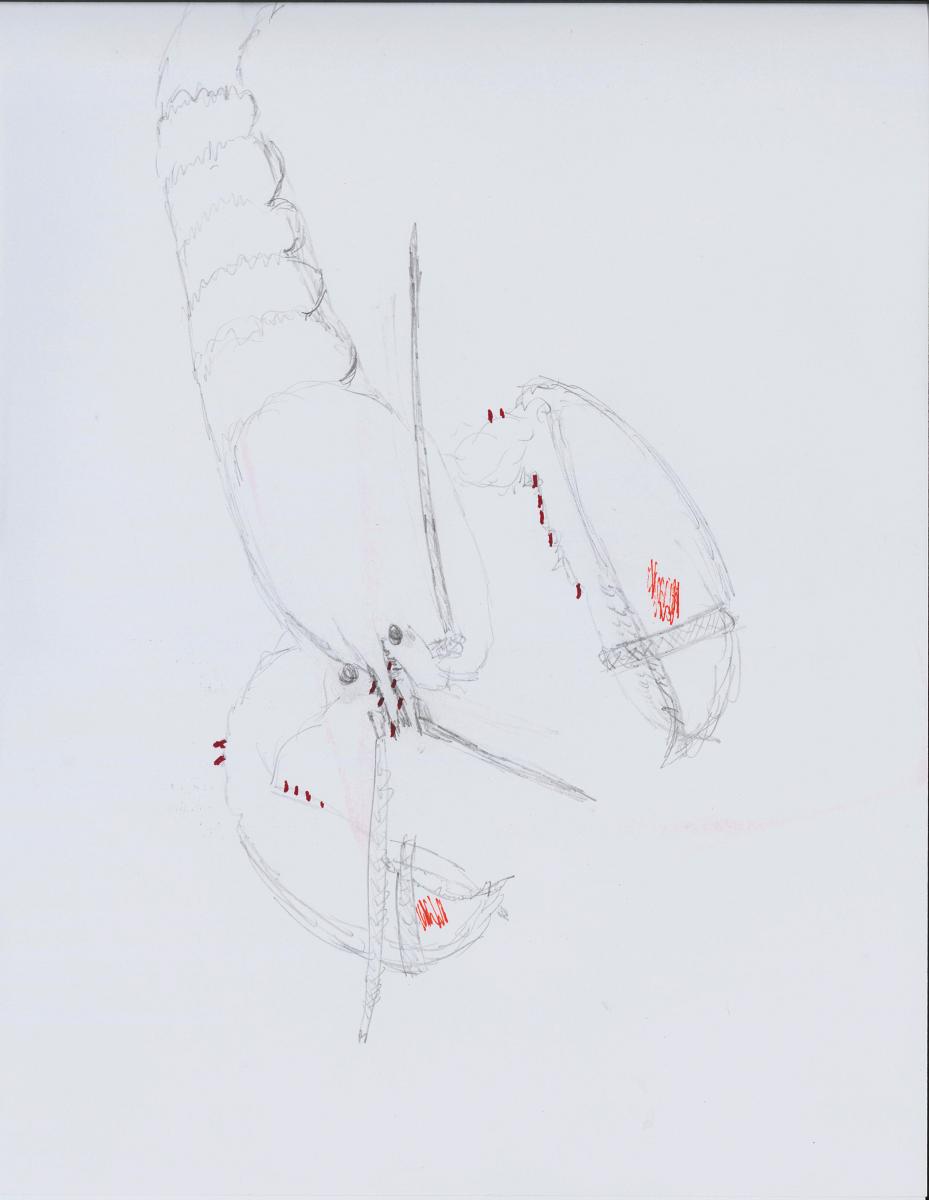

Then we were given pencils, paper, markers, and watercolors and asked to do what Ron called a “scientific” drawing of our lobster. I consider myself a truly wretched artist, so this was particularly tough for me. After spending more time erasing than drawing, I finally produced something that was at least recognizably a lobster. This exercise required me to examine our lobster very carefully and I learned a lot about lobsters just by looking closely. I also learned that if I stuck with it, I could achieve more than I thought. This is part of what educators call an “academic mindset,” which also includes a student’s sense that they belong in an academic community, can succeed at a given task, and that the work has value for them. How much do we miss out on when we just give up because we don’t consider ourselves good at drawing—or math or science? Lots, I’m sure.

It may not hang in a museum, but it sort of looks like a lobster!

After that, we read a very dry scientific journal article about—amazingly—the relationship between a lobsters’ differently sized claws. After having spent so much time looking at, thinking about, and working together with our classmates and our lobster, we were able to unpack the jargon and make sense of complex material. Ron also helped us focus on the parts that we did understand, which was really helpful. Then we read a magazine piece about the ethics of killing and eating a live lobster. Do lobsters feel pain? If so, is it ethical to hurt them? With a vegetarian in our group, this set off a very lively discussion, as you might imagine.

Finally, we presented our poster projects, first to the other members of the class, then in a poster session for participants from the rest of the conference, who cycled through the various rooms to learn about what others had learned that day. Presenting our findings and talking about them helped to reinforce what we’d learned.

By then, it was five o’clock and the day was over. It’s shocking how much I have retained about this day. I’m writing this post a week later and have not had to consult a single note.

By the end of the day, I realized that this was the single most interesting and useful conference I have ever attended. Think of the last conference you attended. How much of it can you remember? How much of the time were you learning something useful (who knew this would be so useful?) and how often were you sneaking a peak at your smartphone or just plain blowing off a session so you could catch up with friends or colleagues? Admit it, most conferences stink.

Then it hit me. Most schoolchildren today sit in classes that are the equivalent of truly lousy conference sessions. Somebody stands at the front of the room and presents a boring recitation of facts and figures. If there’s time for a few questions at the end, great. If not, not. Then the audience gets a few minutes to switch rooms and they start it all over again. All day long, five days a week, for twelve years. Sixteen, if you include college. So we’re sending most of our kids to five lousy conferences a week for twelve years. Then we administer mind-numbing tests on material that was too boring to remember, and those tests become the basis for whether their schools get more money, the teachers get raises, and what kind of colleges the kids attend.

Can you imagine if you were tested on the material presented at two hundred crappy conferences and your test results determined if you got a raise or a promotion?

That’s what we’re doing to our kids.

I don’t blame the teachers. I don’t blame the principals or the parents. It’s not the fault of anybody in particular, but it’s our collective responsibility to fix this. We are teaching our children badly and we’re testing them just as badly.

The good news is that there’s a better way.

This conference was a way of understanding how teaching should be done. Deeper learning gives children the opportunity to collaborate, solve problems, communicate what they’ve learned, master rigorous academic content, and it challenges them to stick with it even if the work is difficult. Schools are already doing it across the country, but they are succeeding in spite of an education system that designs poor curricula, fails to give teachers the tools they need, and administers tests that reveal little about what our kids can do. I know that many, many more teachers and school districts can draw this metaphorical lobster a lot better than they think they can.

As I think back on this really illuminating day, I realize that I have known the technical definition of deeper learning, but I had never actually felt it. It’s exciting, it’s fun, and it’s a great way to learn. I also realized what we all can agree on—that we’ve got to stop sending our schoolchildren to twelve years of terrible conferences. Who disagrees with that?