Letter from President Larry Kramer

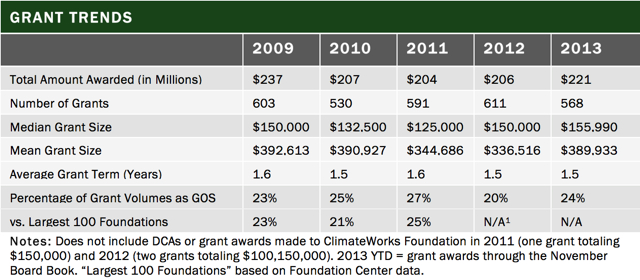

Every November, the Board of the Hewlett Foundation authorizes a budget for the upcoming year, and, as part of that process, reviews what progress we have (or have not) made in our grantmaking strategies during the preceding year. As this requires Board members to absorb a great deal of complex detail, last November we rolled out a new version of the Board Book, designed to make the material easier to follow. (June Wang wrote a post about the Board Book redesign for our blog.) The revised Book included, among other things, a new “overview” that presented data for the past five years on the number of grants, their average size and duration, and the percentage that were for general operating support (GOS). Here is what the Board saw:

These figures raised questions for a number of Board members, who found them surprising in certain respects. Several asked whether our grants had become smaller in amount and/or shorter in duration than they used to be. Others wondered if we were drifting away from the Hewlett Foundation’s longstanding preference for GOS. Still others remarked that it was hard to draw conclusions without seeing the data broken down by program. They asked for a more thorough analysis of our grant trends.

The Board’s reaction stimulated a robust conversation among the staff. Had our grantmaking changed in ways that ought to concern us? Have our grants become smaller or shorter or both? Have we moved away from the tradition of helping institutions through general operating support toward a more controlling emphasis on discrete projects? If so, have these changes affected our staffing or the way we work?

Answering questions like these, we soon discovered, is anything but straightforward. On the contrary, our efforts to do so simply raised more questions. For example, the data we used in November presented GOS in terms of the number of grants, which can be misleading because GOS grants tend to be larger and therefore made to relatively fewer organizations. Would it be more accurate to measure GOS as a percentage of grant dollars? Should the data include Organizational Effectiveness grants, which have become numerous in recent years as part of a concerted effort to help grantees, but are—by definition—small and for a single year? How should we classify something like the extraordinary $500 million ClimateWorks grant, which was GOS and paid out over five years, but booked entirely in the year it was made (thus overstating GOS for that year and understating it for the following four)? Similar complications presented themselves when we focused on other measures, like grant size or duration. Even veteran program staff were surprised by the number of potential variations and complications that emerged in our conversations.

We concluded that a more thorough analysis of our grant trends was called for. To that end, we enlarged our review to cover the past ten years, instead of five. Beginning in 2004 made good sense: by then the Foundation’s endowment had recovered from the bursting tech bubble and incorporated the assets of Bill Hewlett’s estate, and the first stabs were being made to formulate and implement Hewlett’s distinctive brand of “outcome-focused grantmaking.” In addition to making it a ten-year review, we asked the programs to make separate presentations to explain how and why their grantmaking evolved as it did, incorporating a narrative alongside the statistics. We gave each program thirty minutes with the Board at our July meeting, during which they walked through the past decade of grantmaking and described the kinds of things that had shaped their particular outcomes. The memos they prepared for this purpose are below.

Grantmaking Trends Memo: Education 2014

Grantmaking Trends Memo: Environment 2014

Grantmaking Trends Memo: Global Development and Population 2014

Grantmaking Trends Memo: Effective Philanthropy 2014

Grantmaking Trends Memo: Performing Arts 2014

My task, at the conclusion of these presentations—which we interspersed with other business over the two-day meeting—was to draw things together and make some sense of the overall picture that emerged, if one emerged. (It did.)

I want in this letter to share what we found. Let’s start with a snapshot of cumulative grant trend data for the Foundation as a whole, together with data for our five major programs. As we did with the Board, we include only our major programs: Education, Environment, Global Development & Population, Performing Arts, and Philanthropy. We left out “Special Projects”—a residual category of mostly one-time, one-off grants—and a handful of small, stand-alone initiatives on the ground that these are too small to analyze separately and idiosyncratic by nature, and including them needlessly clutters the data. (In case you are wondering, however, leaving them out has no effect on the overall analysis.)

Here are the charts (click on the right and left edges of the charts to move forward and backwards through them):

Certainly one can construct a story about the Hewlett Foundation’s grantmaking practice and culture around these trendlines. It is, in fact, relatively easy to generate any number of plausible theories to explain the data. But such interpretations must be approached warily, for they are likely to be misleading and overstated. In some respects the program-level data track the cumulative data, but the results for each program also deviate significantly—both from the Foundation as a whole and from each other. We get very pretty graphs as a result, with colored lines that zigzag and crisscross. But the zigging and zagging suggests that other things are driving the data, a point corroborated by comparing the programs’ individual memos and presentations. In the end, the cumulative results are nothing more (and nothing less) than the serendipitous outcome of combining five individual stories: stories that share some things in common but are each also affected and shaped by idiosyncratic factors.

Examining these individual stories carefully tells us much about grantmaking at the Hewlett Foundation as a whole. It reveals important shared themes: both a general way of approaching the grantmaking process and certain internal and external factors that operate in common across programs. But the stories equally bring to light additional influences that shape grantmaking differently in different programs and at different times. The overall picture is of a Foundation whose grantmaking practice is complex—something only to be expected given the breadth and diversity of our work—but that still reflects and preserves important core values (what I’ll call “the Hewlett Way” below), and whose staff learn from experience and continually adapt to ensure we are effective.

There is a “Hewlett Way” of approaching philanthropy and grantmaking, close cousin of the celebrated “HP Way” that Jim Collins, in his introduction to Dave Packard’s book of that name, called Bill Hewlett’s and Packard’s “greatest idea.” Key principles defining the HP Way included concern for the well-being of communities and not just for maximizing profits; an insistence on superior performance and results; and a belief that the best results come when you get the right people, trust them, and give them freedom to find the best path to achieve objectives.

There is a 'Hewlett Way' of approaching philanthropy and grantmaking...

These same principles animate the grantmaking culture and practices of the Hewlett Foundation. One sees them in our commitment to choosing problems that matter, even when the odds of success are long; in our commitment to setting goals and holding ourselves accountable for making progress toward those goals; and in our commitment to finding the right organizations, trusting them, and giving them freedom to find the best path to achieve objectives.

A. General Support: Enabling Rather than Controlling Grantees

This last commitment—to which one should append a proverbial “but not least”—is embodied in the Hewlett Foundation’s longstanding preference, whenever possible, to provide organizations with long term, general operating support. In a typical year, 65-70 percent of our programs’ grant dollars are given in the form of discretionary support, whether to a whole organization or to a program within an organization that pursues multiple missions. Moreover, that figure understates the reality for at least two reasons:

First, seven to ten percent of our grants each year go to grantees we can support only under the rubric of “expenditure responsibility” (typically because the grantee is a non-U.S. entity). The IRS requires that these be project grants, even though many could presumably be for general operating or program support.

Second, for reasons that require a bit of explanation, the apparently low GOS figures for our Education Program are misleading. Many organizations have multiple missions, often pursued through separate programs or centers within the organization. By way of illustration, Stanford University comprises a number of separate schools, institutes, centers, and so forth. If we give an unrestricted grant to the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE), the grant is to Stanford University as a formal and legal matter, and the IRS requires us to report it as a project grant for tax purposes. For all practical and other purposes, however, it is discretionary support and so like GOS from the perspective of SCOPE. Internally, we label this “general program support” and treat it as GOS. Or, rather, that has been the practice in all our programs except Education, which approached this conservatively and classified most of its general program support as project support. That difference matters insofar as it conveys an inaccurate impression of the Education Program’s grantmaking. We cannot now go back and recode the entire last decade, but to get a sense of the difference we reviewed the Education Program’s 2013 grants. We found that, last year, 48 percent of the Education Program’s grants and 65 percent of its grant dollars were for general operating or program support, placing Education squarely in the same range as our other programs.

We believe—and this conviction is deeply grounded in the Foundation’s culture—that there are good reasons for finding strong institutions to which we can give long-term general support. To begin, it reflects an appropriate modesty on our part. After all, however much research and analysis we do, we still are working far from the front lines. The organizations we support (not to mention the beneficiaries they support) often have experience and knowledge we lack. Even where program staff worked in the field before joining Hewlett, as is normally true, our grantees are living with the issues up close on a daily basis, meaning they are better situated than us to make judgments about tactics and to adjust swiftly to changes on the ground. More important, organizations generally do better—making them more likely to achieve the goals we mutually seek—when they have flexibility and freedom to find the best path forward. If micromanagement is bad management within an organization (and it is), how much worse is it when exercised from afar? Both we and our grantees are stronger the more we enable rather than control what they do.

It is critically important to bear in mind that GOS is a means and not an end. Our intention is to find the best way to enable grantees to accomplish goals we both share, which in some circumstances may legitimately point toward grants that are shorter or smaller or project based. Some of these are described in the memos from the individual programs: Project support may be called for to ensure proper alignment between our mission and that of a particular grantee, for example. Or sometimes a grantee prefers project support for budgetary, legal, or internal management reasons. Sometimes a particular grant is part of a larger grant cluster, as when we make small project grants in support of the work of an anchor grantee who is receiving long-term GOS. The range of the Foundation’s work necessarily requires us to contend with a multitude of constantly changing circumstances and situations, making generalization impossible and, indeed, counterproductive.

But the touchstone—the objective for which GOS itself is but a proxy—is the extent to which our grantees feel empowered (as opposed to limited, manipulated, or controlled) by our support. And it is here that the Grantee Perception Report is helpful, because we do well along all relevant dimensions. Particularly noteworthy are strong scores with respect to such questions as whether we treat grantees fairly, whether grantees feel pressure to alter or deviate from their priorities, and whether they find our process burdensome. In all these areas, we rank in the highest quartile or better among all foundations and at or near the top of our peer cohort.

B. Getting Results: General Support and Strategic Philanthropy

These grantee perceptions matter because—like its elder HP relation—the Hewlett Way of doing philanthropy also emphasizes performance and results, which in the foundation world is what people mean when they talk about the need to be “strategic.” A lot of ink has been spilled debating the merits and demerits of “strategic philanthropy,” most of it generating (as they say) more heat than light. But the core idea is simple and compelling: The Foundation’s resources are limited and precious, and we have an obligation to our founders and to our society to use them effectively. At a minimum, this requires making grants for and with a purpose, so as not to dissipate our treasure in a scattershot or pointless manner. We must identify goals and be honest in assessing whether we are achieving them. Most large foundations share these views, of course, though everyone has their own lingo for them. At Hewlett, this is what we mean when we talk about “outcome focused grantmaking.”

There is a mistaken view that it’s difficult to utilize long term GOS while being strategic—mistaken because it oversimplifies a complex process and calculus. Rather than standing in tension, our twin commitments to providing general support whenever possible and to being strategic inform and augment each other. When integrated thoughtfully, they make us more effective.

We begin with the problem: with an issue or challenge that the president, Board, and staff believe the Foundation can and should address. This point matters. Too many philanthropists today begin with some tool or device they want to employ—“impact investing,” “philanthrocapitalism,” “catalytic philanthropy,” pick your poison—and then look for a problem on which to use it. This turns the process on its head. We start by identifying problems we believe we should tackle, a question of values, and then ask whether we can make a difference and what tools we need to address those problems—looking for partners if our capacity to have impact while acting alone is limited or if some of the necessary tools are outside our experience or expertise.1

We begin with the problem: with an issue or challenge that the president, Board, and staff believe the Foundation can and should address.

As noted above, an important part of the Hewlett Way is choosing problems that matter. History and past practice provide guidance, but within our areas of interest and expertise we take seriously the responsibility to take on difficult problems, especially when others cannot or will not do so. One sees this reflected in every area of the Foundation’s work—from setting out to mitigate climate change globally to protecting abortion rights, working to change the focus of K-12 education, tackling political polarization in Congress, and more. Every one of these is a risky proposition—undertaken with awareness that success is far from guaranteed, but with a resolute sense that someone needs to try.

Developing strategies to crack these sorts of problems requires articulating clear goals, developing a story or argument about how to achieve those goals, determining what resources exist or are needed to succeed, articulating how we’ll know whether we are making progress, and preparing to adjust based on what we learn as we proceed. This is the “hard-headed approach to soft-hearted goals” embodied in Hewlett’s distinctive approach to strategic grantmaking.2

The tricky part comes in implementing a strategy, and it is here that the interplay between our efforts to achieve results and our preference for long term general support becomes important. As one sees from the individual program memos, the typical strategy has a more or less predictable lifecycle. The first few years are characterized by uncertainty and experimentation. No matter how well we’ve done our homework, no matter how precisely we’ve tried to articulate our theory of change, no matter how thoroughly we’ve scanned the field, it is only when we start making grants and seeing up close how different grantees perform that we can determine where to make deeper and longer investments. The early stages of a new strategy thus normally have a large proportion of grants that are project based and, for this reason, shorter and smaller.

That isn’t always true, of course. Some strategies lend themselves to general support more easily than others, even in the early, experimental stages. This is true, in particular, where the strategic goal itself is to support some kind of institution (as opposed, for example, to producing a change in public policy). The core purpose of the Performing Arts Program’s “Continuity and Engagement” strategy is to ensure ongoing support for arts organizations in the Bay Area; the Philanthropy Program’s “Knowledge Creation and Dissemination” strategy likewise aims to support academic centers, journals, and nonprofit organizations that are in the business of generating research, analysis, and tools to improve philanthropy. Though grants may grow longer and particular recipients shift after the first few years, strategies like these can incorporate relatively high levels of general support from the outset.

But most of our strategies aim for a policy outcome of some sort, which requires finding organizations that are effective in moving policymakers or in helping to create the conditions to do so. As there seldom are single organizations that cover all the bases or are capable of realizing our ends entirely by themselves, we identify and support clusters of organizations—cultivating an institutional ecosystem—that can, cumulatively, achieve our strategic objective. As a result, we typically begin these strategies by testing alternative approaches and experimenting with different organizations and combinations of organizations: things best done with shorter term, project grants. For similar reasons, we expect to go through a courtship period with many new grantees, as we look to confirm alignment between our respective goals before committing to a deeper relationship in the form of long-term general support.

As time passes and we learn more, we can begin to reduce the number of grantees and shift to grants that are less restricted, larger, and longer. Indeed, the failure to move toward or achieve this kind of shift may itself be a sign that a strategy is faltering, a kind of canary in the mineshaft. This was true, for example, of the Philanthropy Program’s Nonprofit Marketplace Initiative, which we recently brought to an end. That said, even when a strategy is fully mature, we still would not expect our grant portfolio to consist only of such grantees. In part, that’s because (as noted above) implementing strategy invariably requires support for and from many organizations doing different things, including some whose role is more targeted or limited in scope. But mostly it’s because the process of experimentation and learning continues even in mature strategies, and we always remain open to new ideas and to giving a chance to organizations with new projects or approaches. Just as it’s a bad sign if a mature strategy has few or no grantees with long term GOS, it’s a bad sign if a strategy has only such grantees, which should alert us to the possibility that we’ve become complacent.

In actual practice, grantmaking is seldom as straightforward as this idealized account, and a variety of additional factors influence or confound what grants are made. Some factors affect all programs equally, such as the dynamics of our budgeting process and major economic events. Others affect different programs or different strategies in different ways and at different times. The former influences explain why some grantmaking shifts occur in tandem across programs; the latter explain why most do not. Inasmuch as factors like these are inevitable—an inherent part of the philanthropy landscape—we must expect this degree of messiness. What is, indeed, remarkable has been how and how well the Foundation’s program staff have adapted and adjusted to these sorts of pressures without losing sight of either our strategic goals or our preferred approach to working with grantees.

The discussion below touches on some of these factors. It is not meant to be exhaustive but simply to illustrate a few of the additional dynamics that further shape grantmaking decisions.

A. Common Causes

The way in which the Foundation tracks program budgets has important effects on the number, size, and duration of grants. In particular, a grant is fully charged against a program’s budget in the year it is made, regardless of when or at what pace the grant will be paid out. Now, suppose that a program officer would like to give a particular grantee $300,000 over a three-year period. Apart from administrative burdens—no small matter, but something we can put aside for purposes of this illustration—there is no material difference to the grantee between three consecutive one-year grants of $100,000, and one three-year grant of $300,000. Not so the program officer, because the three-year grant reduces his or her grantmaking capacity in the year the grant is made by three times as much. Of course, for the very same reason, a three-year grant will increase grantmaking capacity by $100,000 in each of the subsequent two years.

This opens the door to a variety of potential tradeoffs: we can make grants smaller in order to make them longer, or we can make grants shorter in order to make them larger. Longer grants are generally larger grants, which means supporting fewer grantees. And so on.

The point is subtler than it might seem at first. Tradeoffs between the size and number of grants are unavoidable, at least so long as budgets are limited. But choosing to book our grants the way we do puts grant length into the mix as well, increasing the number of tradeoffs that must be considered and complicating the decision-making process.3

Tradeoffs between the size and number of grants are unavoidable, at least so long as budgets are limited.

These effects and tradeoffs—referred to in wonkish circles as “budget hydraulics”—constitute an important, and inescapable, consideration in our grantmaking. Examples are found throughout the individual program memoranda, from the Environment Program’s decision to limit large GOS grants to one year so it can make more such grants, to the Education Program’s ongoing shift to fewer grants so it can make those grants longer and larger, to the triennial spike in the Performing Arts Program budget following its decision in 2009 to adhere to three-year grants.

Budget hydraulics are unavoidably entangled with our efforts to achieve philanthropic goals. As noted above, most successful strategies are built around some number of anchor grantees to whom we make long-term commitments and provide substantial general support. But our strategic ends can never be fully achieved by these grantees alone, and we invariably find it necessary to include other organizations for supplemental and supporting work, such as filling research gaps, helping test new propositions, and so on. Often, there are a great many such grantees, supported by grants that tend to be shorter, smaller, and project oriented.

Making the necessary tradeoffs among grants and grantees—deciding who should get what kind of support and for how long, given consequences for the funds available to other grantees—requires judgment that is shrewd and balanced and informed by deep knowledge of the field, the strategy, and the grantees. Complicating matters further, the grantmaking environment itself is constantly changing. Consider the nuanced choices (described in the program memoranda) that were necessary to ensure progress in our efforts to promote OER and Deeper Learning, to enhance the transparency of governments around the world, or to mitigate carbon emissions—all undertaken as political grounds were shifting and organizations were evolving, emerging, and disappearing.

General economic developments are another factor influencing every program’s grantmaking. Ordinary economic growth or shrinkage is accounted for by our three-year smoothing formula for determining the overall grant budget and has little effect. But major economic dislocations, both up and down, are a different matter—particularly in combination with the budget hydraulics described above.

Growth is relatively easy to handle, even precipitous growth such as occurred in the years prior to 2008. Pretty much everything went up in those years. There were many more grants, and those grants were both somewhat longer and considerably larger—though in different proportions from program to program, depending on the program’s strategies, the state of the field in which it was working, the availability of good organizations, and the like.

Downturns are harder, and the 2008 crash had devastating effects on every program. Implementing budget cuts of 40 percent over a two-year period was a profound shock to the system, highlighting and exacerbating the difficult choices required by our budget hydraulics. For the most part, program staff followed then-President Paul Brest’s direction to reduce the number of grantees and cut whole strategies rather than give everyone a “haircut.” But following this approach exclusively proved impossible. Forty percent is a big number, and all the fat and even some bone and muscle had been cut well before it was reached. At some point, further cutting in this mode threatened vital organs. As a consequence, each of the programs instead found itself constrained to reduce grants to organizations that were too important to be wholly cut off.

In most cases, these reductions were accomplished by keeping grant size steady while making grant terms shorter—the net effect being to create a cadre of grantees in each program that receive regular support but are now locked into an annual grant renewal cycle. I say locked in because program budgets have been mostly flat since 2010, leaving little flexibility to extend grant terms without eliminating other grantees or forgoing necessary new work. This might be unimportant were it not for the fact that annual renewals needlessly increase the administrative burdens both on us and on our grantees. I describe a solution to begin undoing this in Part IV below.

B. Episodic Influences

On top of factors like the economy and budget hydraulics, grantmaking is shaped by a wide range of other factors that operate in less predictable ways. These may touch some programs but not others or affect different programs at different times and in different ways. Some of these factors are positive and helpful; others create problems. Either way, they can be significant forces in determining what we do and how we do it. The brief discussion that follows is by no means comprehensive, but it does illustrate the sorts of forces and conditions we are inevitably constrained to take into account.

The state of a field in which we are working can make a huge difference in how we work. The grantees available in an old and established field are different from those found in a new or emerging one. Older fields are populated by large, well-established organizations, often with multiple missions and capacities. This can be an advantage when our strategies line up with what these organizations already do, as in the population field, but it can make things difficult if our strategy involves something novel.

Our work in education nicely illustrates the latter situation. The education field is populated by large organizations that have long relied on particular approaches and are slow to change. One way to get around this is to build or develop new organizations, which is essentially what we have done in our OER work. The OER subfield was launched at MIT a decade ago, with a large grant from the Hewlett and Mellon Foundations. And while we have been able to accomplish some of what was subsequently needed to grow the subfield through institutions like MIT, much of the work called upon us to develop and nurture new organizations. This required carefully structured grants and took time. Yet we are now on the verge of a breakthrough, with OER poised to become part of the educational mainstream. Much work still remains to be done, but—due in no small part to this earlier field building—we can support the work with larger, longer, GOS grants to some of the very organizations we helped establish.

A different approach was called for in connection with our Deeper Learning strategy. In that context, the emergence of the Common Core State Standards and the array of established institutions already working on them suggested a need for different tactics. We have, to be sure, still done a fair amount of field building, but we needed also to work with and through recognized educational organizations. As explained in the Education Program’s memorandum, at first this entailed extensive use of project support—both to see if established organizations would embrace deeper learning and because GOS would have meant little to these organizations given their size and varied missions. Having done this for several years, we are now finally in a position to begin making larger grants of general support to the best organizations that have adopted Deeper Learning as part of their mission.

The nature of the available grantees may affect grantmaking in a number of other ways.

The nature of the available grantees may affect grantmaking in a number of other ways. In some fields, for example, we can make large grants of general operating support to regranting institutions, which are able to reach smaller grantees better than we can, given our lean staffing. The Performing Arts Program has done this especially well, though the Environment Program has likewise made effective use of regrantors like the ClimateWorks Foundation, the Energy Foundation, and the European Climate Foundation, to name but a few. Our Community Leadership Project has used regranting institutions productively to reach a large number of small nonprofits working in the Bay Area, Central Coast, and San Joaquin Valley.

The capacity of different fields to absorb and use grants is highly variable, and this, too, affects how we work—especially when it comes to developing the networks of interlocking grantees whose separate contributions, cumulatively, are needed to advance a shared goal or strategic end. Doing this well requires an artfully constructed mix of project and general support in grants of varied duration, a mix that must be scrutinized and adapted as the work proceeds.

External developments often influence grantmaking. Some developments open the door to new opportunities that may change the direction of our work. The surprising consensus of state education officials around the Common Core is a good example, as was the Obama Administration’s appointment of OER champions to key positions in education. But external developments can just as easily erode or complicate a strategy. This may be happening in our Deeper Learning strategy at this very moment, as political opposition to the Common Core continues gathering momentum. The difficulties we experienced in our climate work and the need to rethink that strategy had many causes, but foremost among them was the unexpected reemergence of climate change denial as a major political obstacle after 2008.

Sometimes the relevant external event is the entrance or exit of another funder. Our work on abortion rights has been changed and facilitated by the illustrious “anonymous donor,” whose generous support for many of the same grantees has freed us to experiment with new and innovative approaches. In contrast, an influx of new funds into family planning has been a more mixed blessing: new resources dedicated to this underserved field are certainly welcome, but now we must worry about distortions their very size creates in the kinds of services that are offered.

Finally, internal developments at the Foundation sometimes matter. Term limits are generally beneficial, but the frequent turnover of grantmaking staff also has consequences. Outgoing program officers frequently end their tenure by making especially long or large GOS grants to anchor grantees. This is beneficial in giving new program staff running room to learn the ropes, but it can also create distortions. Conversely, because new program officers need time to become fully versed in our strategies and grantees, they may initially favor more short-term project grants.

Gathering and interpreting the data and sharing notes with each other and with the larger staff showed us things about our grantmaking practice that we ourselves had not fully realized. Upon reflection, we think the practice is generally healthy and productive. Still, there is always room for improvement. Learning never stops, and we do not want to become complacent. We have, therefore, used the opportunity presented by this exercise to consider steps we can take to further improve the Foundation’s grantmaking. We have four things in mind.

The first and simplest step is simply to continue what we started, by paying close attention to the Foundation’s grantmaking trends. To that end, we will continue monitoring the number of grants we are making, along with their size and duration and whether they are for project or general support. As our analysis should make clear, there are no fixed benchmarks for any of these indicia: grants may become shorter or smaller or tend toward project support for good as well as bad reasons. But changes in our grant trends may indicate that something unintended is happening, and we can’t evaluate the reasons for any changes that occur unless we observe them first. Early diagnosis is the best way to prevent a small problem from becoming a big one.

Second, as noted above, we presently develop grantmaking strategies according to a specified, ten-step OFG process. It’s an approach that was painstakingly developed and tested over the course of several years, and it has served us well. But every process can be made better, and we now have substantial additional experience on which to rely. We have, therefore, undertaken to review our OFG process to determine how it might be modified and improved. The Effective Philanthropy Group will lead the foundation-wide effort to frame an “OFG 2.0” in the coming year. It will include, among other things, thinking through the whole lifecycle of a strategy, not just its initial formulation. This is not something that should cause anyone, either within or outside the Foundation, any consternation. We do not anticipate major changes, but we do believe we can refine the process to make it better—more flexible and adaptive and so more responsive to the needs of grantees and beneficiaries.

Our third and fourth proposals concern the treatment of small and repeat grantees, whose plight came up repeatedly during our investigation. Each of the programs supports a sizeable number of organizations receiving grants that are renewed annually, often for relatively modest amounts. At present, our grant award, reporting, and renewal processes are formally one-size-fits-all. These work well when it comes to large and complex grants, but they can impose unnecessary administrative costs (on us and on our grantees) in the case of small and/or regularly renewed grants. The Grants Management team is, therefore, working with program staff to develop streamlined procedures for such grants. We have yet to determine exactly what these procedures will look like, or exactly which grants will be eligible. Such decisions must be made carefully, because we don’t want to undermine the strong systems for due diligence and legal compliance that the Foundation has worked so hard to develop. But it doesn’t take an especially sophisticated cost/benefit analysis to see that we can ease the administrative burdens and costs associated with a great many grants.

Finally, we explained in Part III-A how the 2008 economic downturn locked many grantees into an annual renewal cycle. We have developed, and the Board approved, a proposal to partially counteract the effects of the downturn with a one-time “duration fund” of $21 million to be spent over a two-year period. With this, we can restore a large number of these grants—perhaps as many as 150-200—to a three-year cycle, thus saving substantial administrative costs and time for everyone.

* * *

Soon after I joined the Hewlett Foundation, a veteran philanthropist from another foundation said to me that Hewlett “punched above its weight”—and this, he added, even though it was already one of the largest foundations in the world. In part, he was referring to the work we do. But he was also referring to the role the Hewlett Foundation has played in modeling how grantmaking can be done.

There is a 'Hewlett Way' of approaching philanthropy and grantmaking...

There is a distinct Hewlett style of philanthropy that is both supportive of grantees and strategically effective—conclusions reflected in, among other things, the results of our grantmaking, our high rate of general support grants, and the positive perceptions of our grantees and peer foundations. The work we do is not simple: we are, after all, one of the largest foundations in the world, dealing with a great many controversial problems in as many complex fields. But our program staff has done an admirable job preserving the core precepts and values of the Hewlett Way, even while responding to and coping with a host of internal and external pressures.

If we do well—and, after this review, I believe that we do—it is partly because of our commitment to continuous learning. Our current practices are strong, but they can be better, and we are determined to continue improving them.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. © 2014, The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. Photos are excepted from this license, and © 2014 their respective owners, as credited.