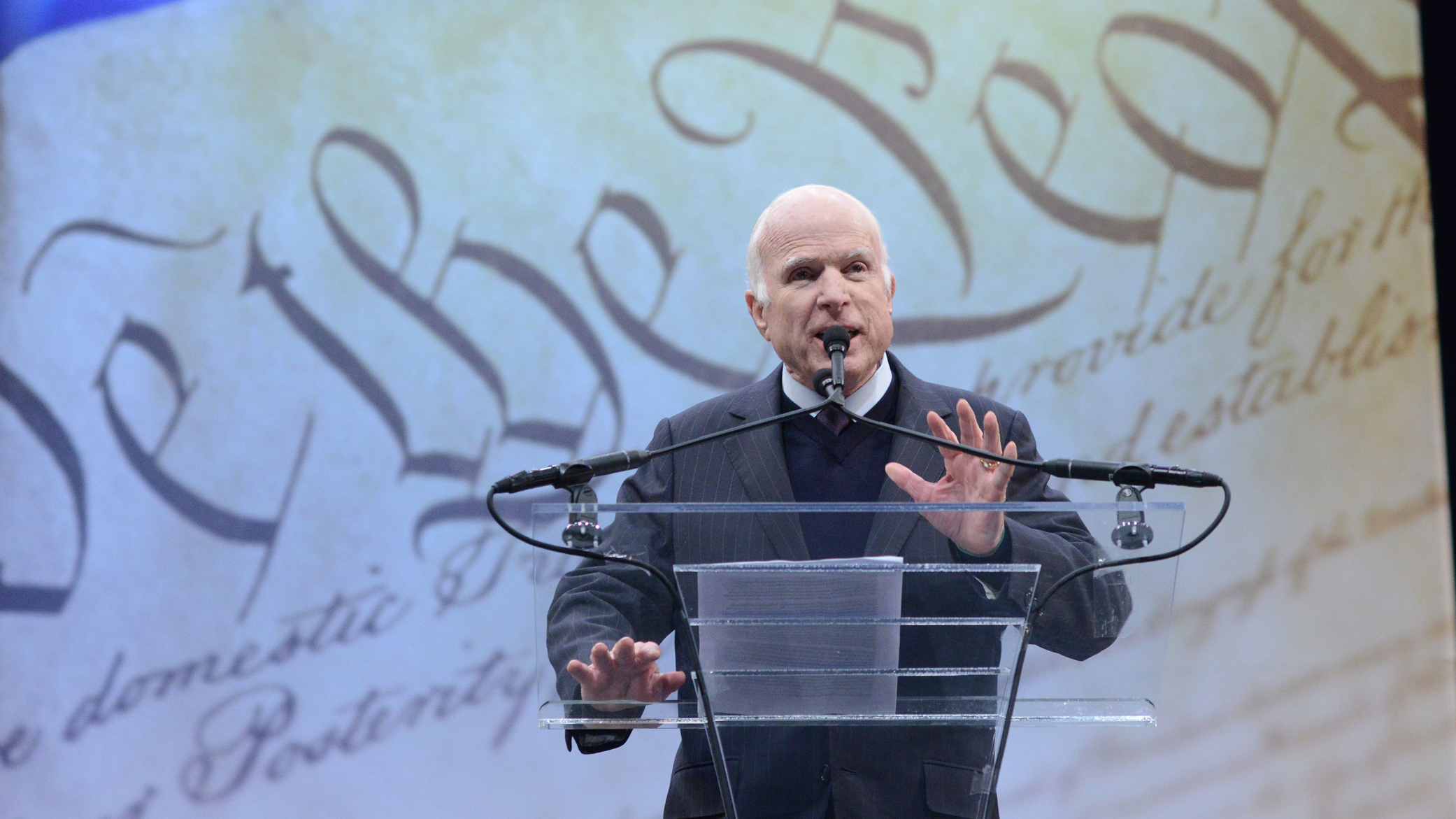

The death of Arizona Senator John McCain has led to a host of tributes far beyond what we would normally expect in the wake of a senator’s passing. It’s due, in part, to the compelling arc of his life story and his eminently quotable style. But it’s also due to the fact that McCain spoke to our democracy’s deepest values, and how they could be realized, in ways that resonated across partisan lines. The outpouring we’ve witnessed this week represents a yearning on the part of many Americans to see those values clearly reflected in our government and politics once again, not clouded over as they are at present.

John McCain was first and foremost a patriot. But his love of America was grounded not in blood – though he spilled so much of his own for it – or soil, but rather in a set of timeless ideals. As he declared in his farewell message, “to be connected to America’s causes — liberty, equal justice, respect for the dignity of all people — brings happiness more sublime than life’s fleeting pleasures.” This gave McCain a capacious and pluralistic view of who could be an American and what would qualify them as such. “You can worship Jesus or Allah or your ancestors,” he wrote in his last book, The Restless Wave. “You can celebrate Cinco de Mayo or St. Patrick’s Day. You can be sentimental and proud of the heritage you brought with you. You can change American arts, food, and industry. Only our ideals remain unaltered. You have to give your allegiance to those.”

Because of his ideals and pluralism, McCain rightly recognized the inevitability and fundamental legitimacy of political opposition in a free society. Reasonable people will disagree on important issues. But that does not mean we should see our political opponents as enemies, members of a threatening tribe that we must destroy (or be destroyed by). This spirit is aptly captured in a video clip from the 2008 campaign town hall when a McCain supporter insinuated that his opponent was not trustworthy, not a citizen, and not fit for the presidency. Without hesitating, McCain took the microphone back and corrected the woman on the spot. Ten years hence, we can discern this same spirit in McCain asking presidents Barack Obama and George W. Bush – opponents who defeated McCain in his two presidential campaigns, and with whom he disagreed on many issues, often vociferously – to serve as his eulogists. For all of their disputes and differences, these three men shared and sought to advance common values of democracy.

Another implication of McCain’s world view is the need for bipartisanship in policymaking. Again from the Restless Wave: “Here’s one fact fools ignore. Our Constitution and closely divided polity don’t allow for winner-take-all governance. You need the opposition’s cooperation to get most big things done. And so, I’ve worked with Democratic colleagues to do things I thought were important. Proudly.” This disposition was reflected in his long service on and recent chairing of the Senate Armed Services Committee, which produces the National Defense Authorization Act each year like clockwork on a bipartisan basis. It was also embodied in the abiding friendships he formed over the years through legislative endeavors with Ted Kennedy, Joe Biden, Russ Feingold, and other Democratic senators.

McCain’s anchoring beliefs in American ideals and pluralism, the legitimacy of political opposition, and bipartisan compromise all led naturally to another abiding conviction: the central importance of Congress as the institution where these values have to be realized for our system of government to work. In his dramatic speech to his fellow senators at the height of the health care debate last summer, McCain defended the burdens and challenges of Congress as embodiments of those facing our democracy as a whole: “Incremental progress, compromises that each side criticize but also accept, just plain muddling through to chip away at problems and keep our enemies from doing their worst isn’t glamourous or exciting. It doesn’t feel like a political triumph. But it’s usually the most we can expect from our system of government, operating in a country as diverse and free and quarrelsome as ours.”

A central thrust of McCain’s speech was to repudiate the notion that Republicans in Congress should defer to the wishes of the president. McCain dismissed this deference as running counter to the logic of our Constitution’s separation of powers. “We are an important check on the powers of the Executive,” he declared. “Whether or not we are of the same party, we are not the President’s subordinates. We are his equal!” He went on to state something that is so obvious that it is routinely overlooked: “We play a vital role in shaping and directing the judiciary, in planning and supporting foreign and domestic policies. Our success in meeting all these awesome constitutional obligations depends on cooperation among ourselves.” For our system of government to work, the first branch of it needs to function – not perfectly, for McCain knew that that perfect is not on the menu with Congress – but more or less serviceably, with a modicum of patriotism uniting the Americans serving in it.

For all the celebration of McCain’s values and life of public service, too many of the reflections this week have had an elegiac nature. It’s as though the senator’s convictions will be buried with him, leaving the rest of us to accept or endure the reflexive tribalism and win-at-all costs politics that, much to his chagrin, have become pervasive in recent years. But that sense of resignation amounts to a rejection of McCain’s legacy, a rejection that many Americans, judging by the response to his passing, are refusing to make. The values that McCain upheld strike a resounding chord at this moment precisely because so many of us still believe in them. As McCain understood deep in his battle-scarred bones, the fight for these values isn’t over – it is really just getting started.