Our work at the Madison Initiative remains squarely focused on improving conditions for dialogue, negotiation, and compromise in Congress. But one question we continue to wrestle with is this: How do we know how Congress is doing?

Some Congressional observers have looked at metrics around “legislative productivity,” bemoaning recent Congresses as the “least productive” ever. But others have rightfully argued that the number of bills passed, alone, doesn’t mean much. Some bills are truly substantive, while some are clearly ceremonial. To complicate matters, still others believe that not passing legislation is sometimes the best reflection of the voters’ interests on an issue.

What else then, might we measure to get a true picture of Congress’ health and effectiveness? Several Madison Initiative grantees have recently taken up this challenge, and we wanted to highlight their efforts with this post.

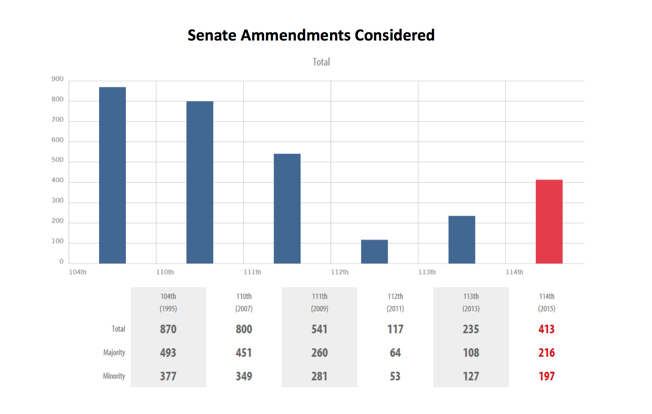

Earlier this year, The Bipartisan Policy Center launched its Healthy Congress Index. The index tracks Congress overall, rather than individual members, and includes factors like the number of working days, the use of the filibuster, cloture filings, and Senate amendments considered, amongst other things, all with the goal of understanding how Congress is governing. It is part of BPC’s Commission on Political Reform, and represents “a first-of-its-kind effort to track, encourage and reward Congressional competence.” The Index tracks back to the 104th Congress, and shows declining performance across most metrics, with 2011’s 112th Congress fairing particularly poorly (see, for example, the chart below showing Senate ammendments considered).

Sarah Binder of the Brookings Institution is taking a slightly different approach to measuring the overall health of Congress. She has created a measure of legislative gridlock that looks at the number of bills passed that address the most salient issues facing the country, with salience determined by things like the frequency of an issue’s appearance in the New York Times’ editorial section.

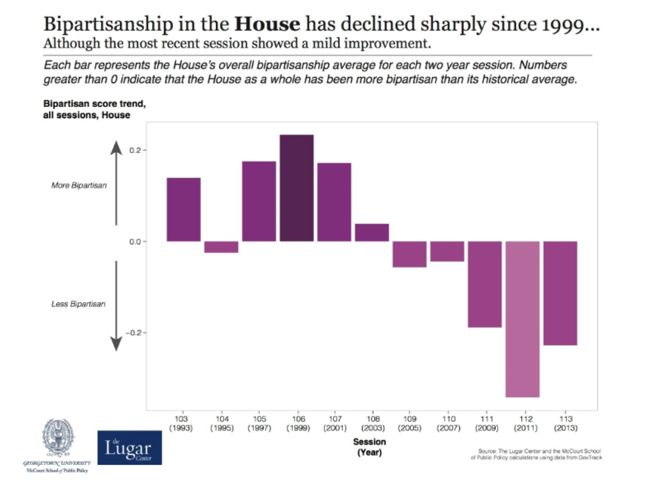

The Lugar Center and Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy recently launched a new Bipartisan Index, intended to develop an objective measure of how well members of opposite parties work with one another. The index measures the frequency with which a Member co-sponsors a bill introduced by the opposite party, and the frequency with which a Member’s own bills attract co-sponsors from the opposite party. It includes data going back to the 103rd Congress and, while the overall trends aren’t looking good (see below), some Members are doing much better than others.

Most recently, the Legislative Effectiveness Project was launched by political scientists Craig Volden at the University of Virginia and Alan Wiseman at Vanderbilt. They have developed a very thoughtful methodology that considers the number of bills that each member of the House of Representatives sponsored and the number of those bills that received any action in or beyond committee on the floor of the House. For those bills that get out of committee, they look at those which subsequently passed out of the House, as well as which become law. The methodology also looks at whether bills are commemorative, substantive, or both substantive and significant. In calculating productivity they control for the Member’s seniority, and whether she was a member of the majority party, amongst other things.

There are, of course, many different ways to get at the health, productivity, and effectiveness of Congress. Each touches on different dimensions of individual and institutional efficacy, and all have their blind spots. Ultimately we’re convinced that a combination of multiple measures will be necessary to truly understand the workings of such a complex institution. We think those highlighted above are pointed in the right direction—and we would welcome your thoughts on these and other attempts to understand Congress’ effectiveness.