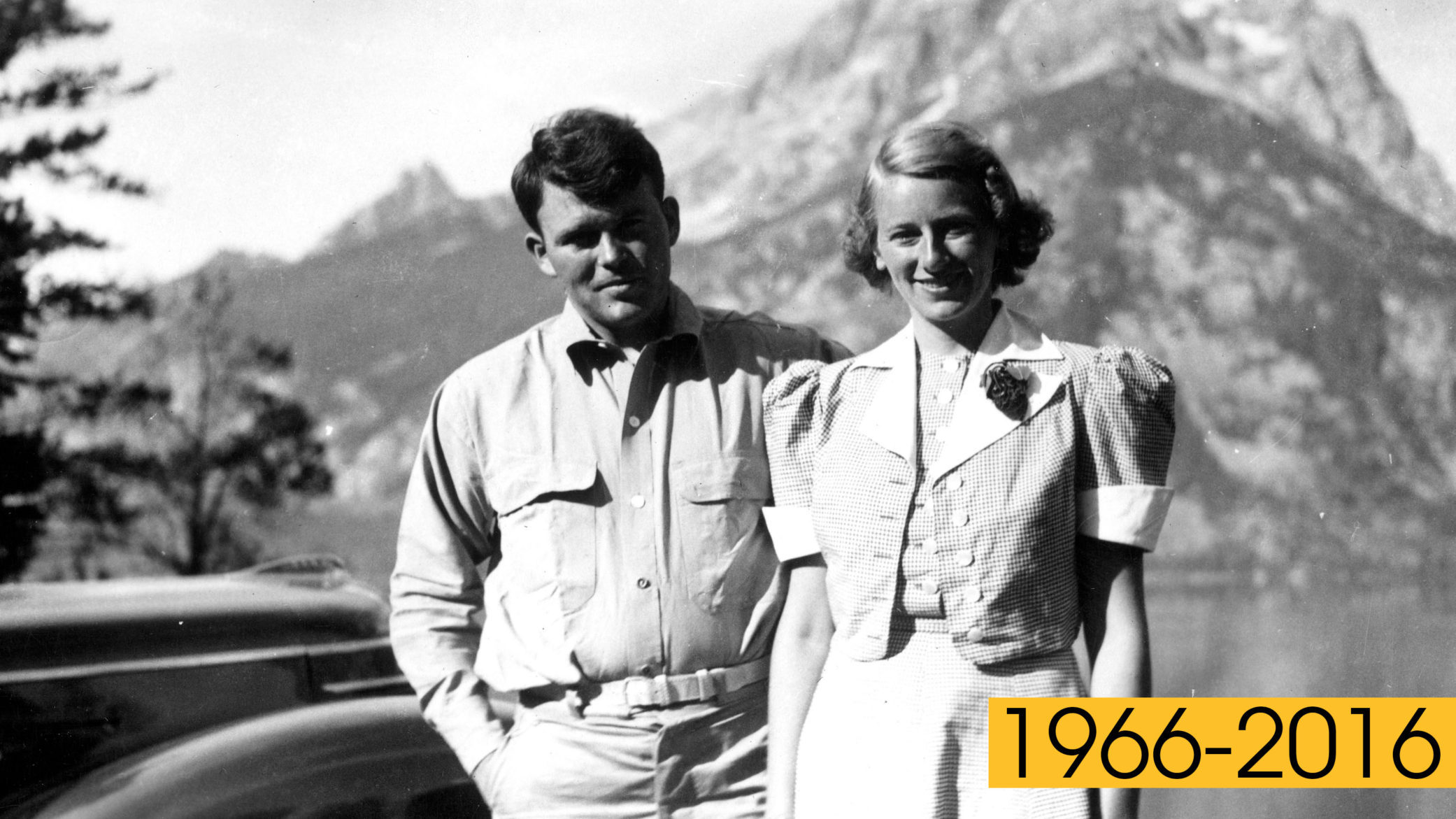

Honoring 50 years of philanthropy

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the milestone has offered a chance for us to reflect and learn from the past, so as to inform and inspire the future.

For our staff and board, “looking back to look forward” has included articulating a set of guiding principles that flows directly from the ethos and values of our founders. In addition, we are reaching out to peers and partners as we think about how we can achieve the long-lasting impact to make the world a better place. We are hosting a symposium in December that brings together leaders from foundations, nonprofits, business, academia and government for a candid discussion about the challenges and opportunities in the social sector.

We also invited former Hewlett Foundation staff — many of whom continue to work in nonprofits and philanthropy — to share their memories of the people and work that transformed their outlook, or made an impact on the broader world. See below for stories from Rhea Suh, Faith Mitchell, Cathy Casserly, Steve Toben, Julie Fry, Guadalupe Mendoza, Bob Barrett, Alejandro Villegas, Erika Ramos, Paul Brest and Natasha Terk.

Rhea Suh: Thinking big on Middlefield Road

Rhea Suh is president of the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy organization with more than 2.4 million members, activists and supporters nationwide. From 1998 to 2007 she worked at the Hewlett Foundation where she designed its energy and climate initiative, led land protection efforts and launched the new constituencies portfolio to focus on environmental justice issues.

Long before the Hewlett Foundation constructed its beautiful headquarters in Menlo Park and became the first LEED gold-certified building in California, the organization did its work out of a small office on Middlefield Road in Palo Alto. It was a modest space and I was part of a staff of perhaps three dozen people in what felt very much like a family foundation. Bill Hewlett, our founder and visionary, was still alive and engaged. His son, Walter, was actively nurturing and growing the foundation.

We came from all walks but were there because we wanted to make a difference. We believed in the foundation’s potential in helping people rise above poverty, providing equal access to quality education, and promoting sustainable policies for a livable world. We were a family that was thinking big and fighting well above our weight.

One of our biggest successes early on was winning protections for the Great Bear Rainforest in western Canada, which was threatened by rapacious logging and other industrial exploitation. We got logging banned on 5 million acres and had another 19 million acres placed under strict sustainable land use protections.

We worked with local coalition partners on the ground and helped build a powerful consensus for change. We worked to empower indigenous peoples, disenfranchised people and entire communities whose voices had been excluded from the economic and political decision-making that shaped their world.

We had to learn to talk to each other, listen to each other and trust each other. Once we were able to do all that, we were simply too strong to be ignored.

The lessons from that experience inspired me to create at the foundation the new constituencies portfolio. It was a way to bring new voices to our environmental work, with the goals of diversity, equity and inclusion at its core. Those voices, in turn, informed our broader mission and approach to the work of others we supported in areas like conflict resolution, natural resources journalism, and environmental advocacy and law. We were able to play a role in strengthening the underpinnings of civil society and promoting solutions grounded in justice.

I look back with deep affection on those days in our cramped office on Middlefield Road. My hope is that the Hewlett Foundation — for everyone who works there now — a place of inspiration that it was for me, and that the vision and work will continue to improve the world, for the next 50 years.

Faith Mitchell: Learning about hares from Bill

Faith Mitchell is president and CEO of Grantmakers In Health, a nonprofit, educational organization dedicated to helping foundations and corporate giving programs improve the health of all people. She led the Population Program from 1987 to 1992 at the Hewlett Foundation.

Do you know there’s a difference between hares and rabbits? I certainly didn’t — until I learned about it from Bill Hewlett.

I knew Bill to be a thoughtful grantmaker, scientific innovator and organizational genius. On a spring day in the early 1990s, I learned he was also an accomplished naturalist.

I started at the foundation in the late 1980s and was the second person to head the Population Program following Anne Murray, who had reached her eight-year term limit and left to launch the Global Fund for Women. My team’s priorities included work on family planning and reproductive health, as well as public education on population-related issues.

Periodically, Bill and his second wife, Rosemary, invited the foundation staff and local board members over for parties. Among other things, these gatherings were an excellent opportunity to get to know the Hewlett family better. One year, we got together for a picnic at the San Felipe Ranch, owned by the Hewlett and Packard families. Located in the foothills east of San Jose, it was roughly the same size as the city of San Francisco.

The picnic was friendly and low-key, in keeping with the Hewletts’ style. We ate on tables inside a barn, and then toured the ranch in a fleet of weathered Willys jeeps. My husband Archie and I rode with Bill, who drove, and his sons Walter and Jim. As the road wound through hills and woods, Bill shared all kinds of detailed information about the local animals and plants. It was my first exposure to his extensive knowledge about the natural world.

At one point, a small creature hopped across the road and I commented, “Hey, a rabbit.” “That’s not a rabbit, that’s a hare,” Bill corrected. Who knew? Was the difference that obvious? His tone was not unkind, but nonetheless, I was slightly embarrassed to have revealed my ignorance.

When we stopped at the ranch office, Bill explained more about hares and rabbits. He also showed us his extensive archive of observations about San Felipe’s plant and animal life. It was filed on hundreds of 3×5 cards. That archive cemented my appreciation of Bill Hewlett’s remarkable intellectual breadth and vision—qualities also reflected in the Hewlett Foundation.

So, what is the difference between hares and rabbits, you’re wondering? It turns out that even though their appearance is similar, hares and rabbits are different species, something like sheep and goats. Hares are larger than rabbits, have longer ears, are less social, and live above ground. And here’s a surprise: According to the National Geographic, Bugs Bunny has been living a lie. He’s technically a hare, but he burrows in the ground. No wonder I was confused!

Cathy Casserly: Launching the OER field

Cathy Casserly is a Fellow at the Aspen Institute. She was a consultant from 2001 to 2004, program officer from 2005 to 2006 and director of OER initiative from 2007 to 2009 at the Hewlett Foundation.

At a conference in 2005, I referred to the then nascent field of Open Educational Resources (OER) as a “complex tapestry,” with pioneering organizations working diligently to develop their parts alongside each other in the community.

At that time, we couldn’t yet clearly see the full design of the tapestry but we knew that we were creating together a unique and meaningful space, thread by thread. We hoped to stimulate the commons for education — beyond government and the marketplace – into a participatory, transparent and efficient place of sharing.

Walter Hewlett wove one essential thread throughout the tapestry, though he may not be aware. The early launch period was challenging as we sought to “sell” the idea of open licensing of educational content to institutions across the globe. The Hewlett Foundation brand carries a well-recognized standard, and we were being encouraged to use its name to gain traction.

Yet, I recall it was Walter in a board meeting who discouraged the idea of the foundation seeking acknowledgement and too close association with the field, saying something to the effect: “We don’t need credit – it doesn’t matter.” His comment wasn’t a declaration of how to move forward, it was more a statement of fact.

Walter’s idea struck me as spot on. This approach gave ample room for other foundations, organizations and individuals to rightly co-own the development of the OER field. And while in the short term the use of the Hewlett brand would have been helpful, in the longer term, it would have hindered acceptance and adoption since the commons, by principle, belongs to everyone and exists as a result of collective agreed upon norms.

This understated approach is a value that permeates the Hewlett foundation culture, and, I would suggest – its success. It is the recognition that to make a real difference takes more than financial resources, strategic plans and staff acumen. It takes the talents of a diverse array of leaders and global organizations to advance the work. Stepping back and making the space for others to step forward creates the opportunity for real change and lasting impact.

Prior to joining the foundation, I had read “The HP Way” and “How Bill and I Built Our Company” that describe the innovative methods that Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard used to build a great company. The HP Way is about valuing decentralization, appreciating everyone’s contributions, creating conditions of trust and respect, and achieving common objectives through teamwork. The HP Way influenced the foundation, too. And in turn, it influenced me as I carry this lesson throughout my career journey.

I feel fortunate to be an early contributor to the OER field. Thanks to Bill and Flora’s values, and Walter’s insightful reflection, a quiet yet powerful thread was woven into the tapestry at just the right time.

Steve Toben: Turbulence in the late 1960s

Steve Toben is president of the Flora Family Foundation, which supports the philanthropic interests of the children and grandchildren of William and Flora Hewlett. He served as director of the Hewlett Foundation’s Conflict Resolution Program from 1991 to 2000.

The Conflict Resolution Program was the brainchild of Roger Heyns, the first president of the Hewlett Foundation. Roger had a deep interest in conflict resolution based both on his academic training as a social psychologist and his personal experience as chancellor of UC Berkeley from 1965 to 1971.

The late 1960s were years of unrelenting turbulence on the Berkeley campus, and Roger often found himself caught in the crossfire between militant student activists, who called him a “lackey” of the UC Board of Regents, and then-Governor Ronald Reagan, who accused him of being soft on campus radicals.

The Berkeley years were not the only source of Roger’s interest in conflict resolution. His PhD had focused on problem-solving and decision-making in groups. As a dean at the University of Michigan, Roger had provided seed funding to one of the nation’s first research centers on conflict resolution. By training and hard-won experience, Roger had come to believe that the nation’s ability to deal with conflicts of all types could and should be improved. Bill Hewlett agreed with Roger and gave him full license to develop the program.

If Roger was the architect of the program, then its builder was my predecessor Bob Barrett. By the time I arrived, Bob had built a sturdy three-legged stool consisting of support for conflict resolution theory centers, leading practitioner organizations, and associations focused on standards of practice and promotion of the field to the wider public.

The program supported the application of conflict resolution approaches in many settings, including the courts, neighborhoods, hospitals, schools, workplaces, faith institutions and legislatures. Thousands of professionals entered the field of mediation to take cases off court dockets, and thousands more volunteered to mediate cases coming out of community dispute resolution programs. Government agencies were established to tackle deep-rooted social conflicts. A core objective was to level the playing field for those who had often been disadvantaged in the allocation of public resources.

During my years at the foundation, we took the program global, supporting emerging models for Track Two diplomacy and peacebuilding that enabled hostile parties to explore avenues for reconciliation outside of formal diplomatic processes. Many of our grantees were scholar-practitioners who had personally engaged in theaters of conflict and were building theory inductively out of their experience.

The Conflict Resolution Program ended in 2004, but the knowledge and innovations generated over its twenty years of operation remain foundational to work in the courts, government agencies, communities, universities, the private sector and international settings.

Julie Fry: Seeing grantees as partners

Julie Fry is president and CEO of California Humanities, a statewide nonprofit that promotes and supports the public humanities in California through grantmaking and programs. She was a program officer in the Performing Arts Program from 2007 to 2015 at the Hewlett Foundation.

Whenever I heard KQED mention the Hewlett Foundation’s tagline in my early days at the organization, I felt like I was part of something special. Although I had been in philanthropy for the previous four years, my time at the Hewlett Foundation really honed my skills as a grantmaker and strategic thinker. This was due in no small part to learning from the people across the organization as well as other funders, and participating in Grantmakers in the Arts and other networking groups.

In the Performing Arts Program, our focus was on providing general operating support – the Holy Grail of grantmaking – and that enabled me to take a comprehensive, big-picture approach to working with grantees. I appreciated that we saw our grantees as partners. We had resources, such as the organizational effectiveness grantmaking and grantseeker workshops, to provide technical assistance to building grantee capacity.

We were encouraged to spend time with grantees to get to know their many facets through on-site visits, face-to-face meetings, multiple performances and events. I learned how to listen deeply, ask questions straightforwardly, provide feedback with clarity, and be a thought partner.

Over time I helped develop the foundation’s arts education policy and advocacy on the federal, state and local level, and oversaw a portfolio of 120 grantees. My work centered around three areas: the grantmaking process and relationship-building with grantees and potential grantees; field participation and leadership; and good citizenship within the foundation, which involved serving on internal committees and finding ways to work across subject areas.

Underpinning all these efforts was the recognition of how unique it was to be in an organization that values the work of nonprofits and communities so highly. This appreciation came directly from Bill and Flora Hewlett, who cared deeply about the Bay Area and the arts.

There are many Hewlett values and tenets that I have taken with me into my leadership role at California Humanities. Although this organization has a robust grantmaking process, I’ve found it useful to discuss with our program staff how we can more effectively streamline our application process, respond to applicant and grantee needs, and assess program impact. I often use the thinking behind the Hewlett logic model as a way to analyze our efforts as well as those of the organizations we support. And at the risk of outstaying my welcome, I still call upon the expertise of Hewlett staff – from HR to facilities to programs – as I navigate organizational leadership.

I will always think back on my time at the Hewlett Foundation with gratitude for stoking my intellectual curiosity and providing an incomparable learning opportunity.

Guadalupe Mendoza: Building transparency and accountability in Mexico

Guadalupe Mendoza is institutional development director at the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a think tank in Mexico. She was a program officer from 2003 to 2012 and acting managing director from 2011 to 2012 for the Global Development and Population Program at the Hewlett Foundation’s Mexico office.

We live at a time of exponential change. Saying this might seem clichéd, but we are affected in our everyday lives and routines from our work in professional projects to personal experiences.

What did I do to outsmart traffic before I started using Waze in 2013, when Mexico City’s streets were taken over by teachers’ demonstrations? How did I stayed in touch with faraway loved ones before WhatsApp? It doesn’t seem long ago when, working at the Hewlett Foundation, I got my first blackberry, which didn’t work in Mexico at first because the technology was not available here.

Social change, in general terms – is the raison d’être of the Hewlett Foundation – and it requires a lot of patience. It is true that the speed of change is affected by the availability and better use of information technologies, data, as well as the disruptive mindset of remarkable individuals. It is also true that despite a quickened pace, change still takes time.

Mexico started the implementation of its first Access to Information Law in 2003. This was a time when corruption in the country were gauged by perception indices, when citizens were not able to have a copy of their own medical records kept in public health clinics, when nobody could know how government funds were allocated to fight poverty and inequality.

This was also a time that the Hewlett Foundation, supported by its board and leadership, officially launched its Global and Development Program and established an office in Mexico. Through its Mexico City office, the foundation could lever prior investments and connections in the country and test assumptions about the potential of transparency and accountability policies to improve the quality of life of the poorest citizens.

Private philanthropy is always challenged with building strategic opportunities out of shifting circumstances, stock market ups and downs, regulatory changes, leadership and staff transitions, unexpected outcomes, volatility in counties where grantees work, and so forth. The investments that the Hewlett Foundation made in Mexico since 2003 — to enhance and promote government transparency and accountability — were, modesty aside, the foundation for building a new field and a new community of organizations that have been game changers across the world.

When I come across harsh perceptions about the progress of transparency and accountability in Mexico, I suggest a dose of perspective. Do you remember that just 12 years ago we had no way to officially ask the government in Mexico virtually anything? There is still a long way to go, but we have to recognize that we have come a long way!

Bob Barrett: Expanding land trusts

Bob Barrett was the program officer for the Environment Program at the Hewlett Foundation from 1983 to 1991. In 1984, when the Conflict Resolution Program was established, he became its program officer as well.

On my first day, then-president Roger Heyns told me the foundation was growing quickly and suggested being on the lookout for new grantmaking ideas. Soon after I attended a national conference on the expanding conflict resolution field, learning about new approaches to principled negotiation, mediation, and alternative dispute resolution in a wide variety of settings.

While ideas from the conference helped us establish and organize the new Conflict Resolution Program, they also helped to inform expansions in the Environment Program, whose overall goal was to help improve environmental decision-making. So in addition to supporting policy analysis and environmental education at the university level, the foundation began supporting organizations that experimented with collaborative problem-solving.

In my law practice prior to joining the foundation, I had helped to form a local land trust in New York and had seen the value of collaborations to preserve and protect special places locally. This seemed to be another logical expansion for the foundation.

In the early 1980s a movement had begun to protect land through local and regional land trusts. Kingsbury Browne, a Boston attorney was a visionary in this movement. He had taken a sabbatical to visit land trusts around the country and later convened a gathering of leaders from such groups. At the time there were about 400 land trusts, with most located in the Northeast and three-quarters without paid staff.

From that gathering emerged a strong desire for a new organization to support the growth and professionalization of these groups: the Land Trust Exchange, now the Land Trust Alliance. The foundation’s emphasis on general support presented a unique opportunity. A series of foundation grants provided critical support during the formative years, helping this fledgling organization build organizational strength and capacity.

Now more than 30 years later, the foundation can be exceptionally proud of the results. The Land Trust Alliance has about 1,100 member groups, with more than 12,000 staff, 15,000 board members, and more than 5 million volunteers and supporters. Collectively they have saved more than 50 million acres throughout the United States, more than the entire state of Wisconsin.

The Alliance has conceived of many new tools, such as conservation easements to help families pass along farms and woodlands to younger generations with assured protections for stewardship. And it has developed key programs to help land trusts, such as rigorous accreditation, an insurance plan to provide the assurance of adequate funding to defend their conservation easements, and excellent leadership, training, partnership, and publications programs.

Looking back, I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with Roger and for the pleasure of seeing how productive the foundation’s general support has been in the land preservation and so many other areas.

Alejandro Villegas: Promoting sustainable transportation in Mexico

Alejandro Villegas is a consultant on sustainable mobility, air quality and climate change policies. He was a program officer in the Environment Program at the Hewlett Foundation’s Mexico office from 2004 to 2013.

Ironically, my first drive from San Francisco airport to the Hewlett Foundation in Menlo Park was in a Mustang — not exactly an environmentally-friendly car. But I was so nervous that I let the fast-talking employee at the car rental convince me that Mustang was the better option.

When I arrived, I learned that our work in Mexico would be to promote environmentally-friendly transportation while keeping cities in motion. Coming from one of the most polluted cities in the world, I felt more than ready to help advance the foundation’s environment program. I was very lucky to get paid to design and implement real solutions to reduce atmospheric pollution in my hometown.

I felt like a cultural translator constantly looking for ways to promote policies that had been applied in other countries. Why would fuel efficiency standards work in Mexico? What should we change to make the standards more feasible?

Supporting and empowering local NGOs wasn’t always easy. We challenged their traditional concepts when we talked to them about local versus global pollution, or sustainable transportation as a means of improving air quality.

Moreover, Mexican corporations have a concept of philanthropy different from the one in the U.S. Context, culture, religion and wealth make a difference. Having to create philanthropic investment strategies sparked my creativity.

I am grateful to the foundation for allowing me follow my passion and commitment. It strongly supported me to pursue the kind of drastic changes that the Mexican government and society needed to improve air quality and reduce climate change.

I still live in Mexico City and enjoy the 150-km Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) network that moves more than one million passengers every day, or the bike-sharing system that conveniently connects with many metro and BRT stations. Other cities like Guadalajara and Leon have also created or improved their existing sustainable transportation systems.

The Mexican government now has a specific office that funds cities through development banks to plan and build sustainable transportation infrastructure. Hewlett grantees also helped to support the studies used to create the first national climate action plan for Mexico, as well as the first federal climate change law in the country.

Looking back, I feel so proud of my time at the foundation. Its organizational structure and culture foster ingenuity and risk-taking. A lot has been achieved through its grantmaking. Today, I’m as committed as ever to continue working for the shared goals and values around sustainable development and positive social change.

Erika Ramos: Feeling like part of a family

Erika Ramos was a program associate in the Hewlett Foundation’s Mexico City office from 2005 to 2014.

As an employee in the Hewlett Foundation’s only office outside Menlo Park, you might expect that I sometimes felt isolated from the rest of the staff. But from the very beginning, I felt very welcomed, not only by my team in Mexico City, but by the smiles you could almost see of the people supporting me over the phone and by email in California.

That first visit to our headquarters — all the employees from Mexico City would travel there a few times a year for “in-town” weeks with all staff — was wonderful. I learned so much about the work done across our different program areas and the culture of the organization. I was able to put a face to the names of the people I worked with every day. The conversations I started in the hallways, in the kitchen and on my way to the next round of meetings have grown into lasting friendships that I truly cherish.

Those friendships became even more important to me when I received a diagnosis of ovarian cancer near the end of my time at the foundation. I didn’t share the news about my diagnosis or the surgery and chemo-therapy that followed with many colleagues, but those I did were a huge support to me. My treatment was successful, and I had just started another round of maintenance chemo-therapy when news came that the foundation had decided to close the Mexico City office. It made farewell even more emotional for me and the close friends I had made.

After I left the foundation, news of my illness reached the staff. The messages of support and the kindness shown by so many people — people who knew me mostly as the name on an email — made me feel like part of a family.

Paul Brest: My two most memorable moments

Paul Brest is former dean and professor emeritus at Stanford Law School, faculty co-director of the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and co-director of the Stanford Law and Policy Lab. He was president of the Hewlett Foundation from 2000 to 2012.

On a very warm day in the late summer of 2000, Walter Hewlett and Jim Gaither, who were then chair and vice chair of the Hewlett Foundation’s board of directors, escorted me into the meeting room at the foundation, then located in an office park on Middlefield Road in Menlo Park. Every one of our approximately 30 staff members was present.

I was as excited as I’ve ever been in my life. I was nervous. And I was wearing a suit — which didn’t become my daily mode of dress at the foundation. The only person I really knew in the room was Steve Toben, who managed the conflict resolution and environment programs, with whom I had collaborated in supporting the Stanford Center on Conflict and Negotiation. Steve waved and smiled, I relaxed, and we were off to the start of what would become the most rewarding 12 years of my life.

Fast forward to a spring day in 2012 when Larry Kramer went through the same ritual with the now 100-plus staff members gathered in the large conference room in our environmentally-friendly office on Sand Hill Road. I don’t know what Larry was feeling, but I can report that he also wore a suit and that this didn’t become his daily mode of dress either. I was extremely proud and excited as I introduced Larry and told him, with utter accuracy, that he was inheriting the best staff of any foundation in the world.

During these past few years, Larry has built on that core strength, bringing his own extraordinary capacity to lead the foundation in outcome-oriented philanthropy to address some of the most vexing policy challenges of our time.

Natasha Terk: The long handshake

Natasha Terk is the owner and managing director of Adcom Designs/Write It Well, a communication consulting and training firm based in Oakland, Calif. She was a program associate in the Performing Arts Program at the Hewlett Foundation from 1997 to 2000.

In the spring of 1997, after a couple of master’s degrees and a few years of scrappy nonprofit work at a small museum in San Francisco, I received an offer to join the Hewlett Foundation. At that time, Silicon Valley was like a rumbling volcano on the verge of exploding. Highway 280 was not very crowded yet. It was only a year later that Paul Brest would announce in a meeting that there was a new search engine called Google that we should all look for on the worldwide web.

A few months in, I received an invite to the foundation’s summer barbecue. On a perfectly clear summer Saturday, my fiancé and I drove down from San Francisco, turning off 880 and heading over the range. There was a gate out front of the modest ranch house. There were a few scattered trees but there was no swimming pool, no fancy guest house and no slate driveway. A simple lunch was waiting. There were hay rides for kids and games on the lawn.

Bill Hewlett was on the porch in a wheelchair, a shawl draped around his shoulders. His round face was shielded from the sun by a wide brimmed hat, the strap tucked under his chin. A lovely Filipino nurse with long hair tended to him.

I felt I had to seize the opportunity. When would I ever have the chance to meet Bill Hewlett? I introduced myself and mumbled something like: “thank you for all you do and for the chance to be part of it.” All of a sudden, he gripped my outstretched hand tightly. We all smiled politely. And he continued to hold my hand. And we continued to smile politely.

“Ha, ha, Bill, you need to let go,” the nurse said. But he held tight. “Bill, you’re making me jealous,” she tried again. But still his hand held mine. More laughter, smiles.

“Oh Bill, you need to let go now.” But still he held my hand.

Some awkwardness. More uncomfortable moments. Some small talk.

Bill’s hand was then detached — finger by finger — from mine.

He didn’t say anything. But that handshake stayed with me. It was about connection, and connecting deeply, through a gesture as simple as a handshake. And through connection, we can hold on to others, to the things we believe in, to the causes that we care about.

Did I read too much into that handshake? I’m not sure. But I do know that everyone uses Google now. And there are a lot more cars on 280. And I got to shake hands — and make a connection — with Bill Hewlett.