Yes, I’m referring to board books – those triennial, quarterly, or (god help you) monthly volumes that we foundations produce for our boards.

Meant to instill confidence and help boards usefully engage in strategic issues, producing these books can become a heroic effort in its own right – and often the driving force behind a foundation’s yearly cycle of deadlines. But are we really helping our boards understand the progress we’ve made, or the challenges we’re facing, when we force them to wade through 300 pages of text? As one program officer put it, “We should be giving them USA Today, not Anna Karenina.”

Last year our president decided it was time to for a change. Over a period of nine months, we redesigned and rolled out a new set of materials for our board.

What did we change?

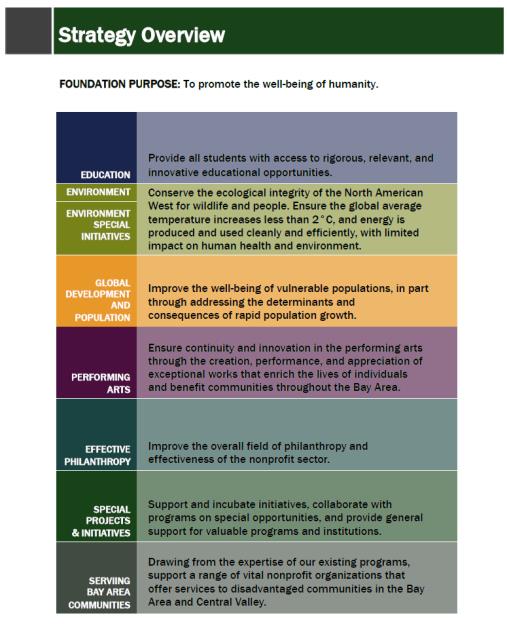

We live and breathe our work each day, but our board – busy people with important day jobs – needed to be reminded each meeting of what we’re trying to accomplish. So we created a series of upfront framing materials – a one-pager summarizing the goals of each program; a timeline of all our strategies and initiatives; a pie chart of our total budget by program area. Each program’s materials also began with a summary of goals and budgets.

We also rearranged and streamlined some things. Traditionally, each program listed their grants in alphabetical order and there was a separate list of paragraphs describing the grants. Instead, we ordered the grants by strategies and then by size so board members could better recognize patterns and clusters of work. We also numbered each grant and put the paragraphs at the back, so board members could easily look up any particular grant they were interested in. We also removed the multi-paged tables in which we painstakingly detailed all the indicators we were tracking for each strategy of our work. Instead, we piloted an approach by which each program rated its progress via a Harvey ball icon (similar to the ones Consumer Reports uses for its ratings), and then wrote narrative text to explain their assessment.

We also rearranged and streamlined some things. Traditionally, each program listed their grants in alphabetical order and there was a separate list of paragraphs describing the grants. Instead, we ordered the grants by strategies and then by size so board members could better recognize patterns and clusters of work. We also numbered each grant and put the paragraphs at the back, so board members could easily look up any particular grant they were interested in. We also removed the multi-paged tables in which we painstakingly detailed all the indicators we were tracking for each strategy of our work. Instead, we piloted an approach by which each program rated its progress via a Harvey ball icon (similar to the ones Consumer Reports uses for its ratings), and then wrote narrative text to explain their assessment.

Last, we made it easier on the eyes. Each program got its own consistent color used throughout the book. It added vibrancy and helped the board visually track our programs. We used fonts that were easier to read (Franklin Gothic and Georgia) and added more photos and charts.

So how’d it go?

You’ll never get it right the first time. When our task force came up with a recommended design that the president approved, everything looked beautiful, perfect, and ready to go. But some things turned out to be harder to implement than we expected and we had to adjust the initial design. One year, later, we are still making adjustments. The Harvey balls mentioned above did show progress in a quickly digestible format, but they weren’t nuanced enough for board or staff. So this year, we are experimenting with a multi-faceted rating system that includes long-term progress, contextual factors, and partnerships. While we think it’s more informative, my hunch is we’ll need to tweak it again next year.

Involve all parts of the foundation, but be clear about roles and decision rules. Within a foundation, the board book touches every part of the building. Take for example, the grant recommendations list—Finance checks the numbers, Grants Management and Legal verify compliance and structure, Programs take responsibility for the content, IT creates the software that generates the list, Communications reviews wording, and the President’s Office manages the whole process. We assembled a cross-foundation task force for designing the book, but when the inevitable questions arose during implementation, it wasn’t clear who was responsible for answering those questions or making those decisions. Was it still the design team? If not them, who? Was it the president? Was it those implementing the changes? Being clearer up front about roles and decision rules during the iterative implementation phase would have saved a lot of confusion.

Think holistically. When we started this process, we limited our scope to revising the November board book, our “big” book, in which budgets are approved and annual memos are written. In the process of re-designing the November book, we realized that the other books all referenced the November book. It didn’t make sense to re-design one without considering the others. So we ultimately revised our scope to work on the other two so that the books were not disjointed. Luckily, our task force agreed to stay on for this additional work.

We didn’t make our ultimate goal of cutting our board book in half, though we did get it down to 126 pages, from 194 the year before. Even so, I feel exactly the way one board member does: “ I don’t miss the old book at all.”

Do you love your board book? Or have a good board book revision story? We’d love to hear about it in the comments below.