Think tanks have tremendous potential to strengthen economic and social policy around the world, using data and analysis to answer questions about how to grow economies, share prosperity, and protect the environment. It is within think tanks that skilled analysts pull apart the most pressing policy problems, examine the impacts of policies, and translate the best available evidence from around the world into a local context. But to fulfill their promise, think tanks need well-qualified staff with the wherewithal to build long-term research programs, and they need to be able to respond with information and advice when unexpected policy opportunities arise. In other words, to fulfill all that potential, they need core organizational support and cannot just live project-to-project.

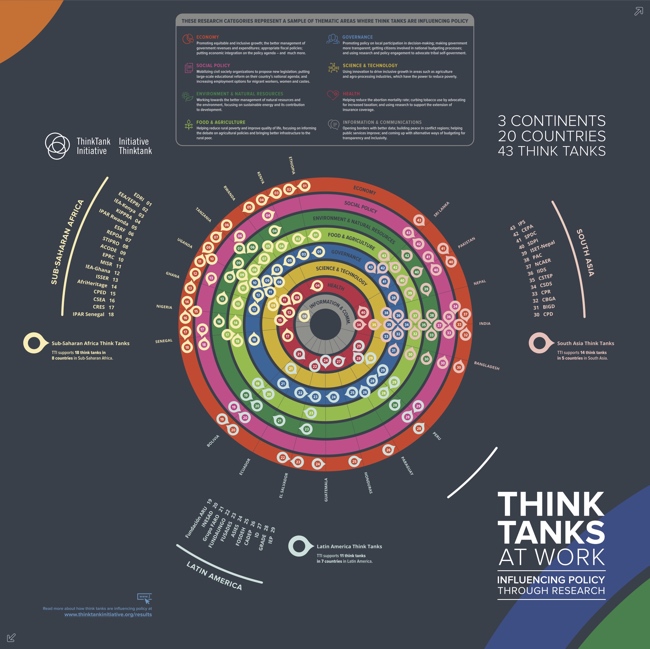

This week, my colleague Sarah Lucas and I have been in snowy Istanbul at the Think Tank Exchange, a gathering of 40-plus think tank leaders convened by the Think Tank Initiative (TTI). Along with the British and Norwegian governments, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Canada’s International Development Research Centre we support TTI. Through it, we and co-funders provide core support to think tanks in Latin America, South Asia, and Africa. This conference was a chance to see what our grant dollars are paying for—and we like what we’re seeing.

Talking to the extraordinary men and women who run these organizations, I heard time and again that core support is the lifeblood of think tanks, whose success depends on credibility and relevance. When an organization has resources that are not all tied up in specific, short-term projects, it can recruit the best researchers and give them the independence to pursue research on policy questions that no particular funder has yet prioritized. With core support, a think tank can ensure continuity within a research program, consolidating the organization’s reputation for being a “go to” source on a topic. It can invest in basic research infrastructure—library services, development of an economic or environmental model for policy simulations, statistical support—that yield benefits for multiple research projects. And the organization can marshal a response when, with the election of new political leadership or a boom in government revenues, a window opens up for new ideas.

Those benefits are not just theoretical. In Ghana, the Institute for Economic Affairs led the development of a framework for transition in executive branch. In Senegal, the Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rural got food security and rural development on the political agenda. In India, the Center for the Study of Science, Technology, and Policy worked with India’s Bureau of Energy Efficiency on a program to promote energy efficiency within large industries. And there are 50 more examples like this from the members of the Think Tank Initiative—just in the past couple of years.

Funding think tanks is quiet and wonky, and there are days when it feels like an agonizing blend of academia and politics, a crazy mash-up of research methodologies, regulatory minutiae, and ministry personalities. There are no ribbons to cut, or announcements about how many microloans were offered or lives saved. Even when think tanks have major accomplishments to their name, they resist bragging because maintaining a relationship of trust with policymakers often requires letting others take credit. For that reason, it is hard for think tanks to be recognized by funders for the value they bring.

But like us, our fellow Think Tank Initiative funders do know there’s a very high pay-off when people who care about getting the facts are able to influence political decision makers. When think tanks find their voice—and that’s happening more and more, as the appetite for evidence and technical advice increases in many countries—there’s no question that they are key contributors to national policy debates. Think tanks deserve the level and type of funding that will let them do their best work. They deserve core support.