Demographic portrait of grantees: What we’re learning and doing to support inclusion and improve our practices

We recognize, too, that numbers tell only part of the story. The insights and experience of board members, staff at every level, grantees, and the communities in which they work are critically important, and we must take a holistic approach—one that is thoughtful, authentic, and substantive—to meet our aspirations.

Here are some of the concrete ways in which we are acting on what we have learned:

Heeding the demands of equity as new strategies are developed. Questions related to diversity, equity, and inclusion are being asked and more intentionally incorporated into Hewlett’s outcome-focused philanthropy approach. For example, the grantee portfolio of our Environment Program’s Wildfire Strategy, launched in late 2020, has been built from the outset with DEI in mind—focusing, in particular, on the leadership and knowledge of tribes, as well as on organizations dedicated to diverse and inclusive coalition-building. Meanwhile, program staff in our Global Development & Population Program, which includes some of our longest-standing strategies, have put equity at the core of their ongoing strategy refreshes—taking a close look, in particular, at ways to shift power, support voices in Africa, and build more equitable partnerships. Similar work is underway in all of our programs, which are investigating how systemic racism shows up in their respective fields and looking for ways to address it in our grantmaking that will improve our capacity to achieve our goals and outcomes.

Commissioning data-driven research to guide practices in specific fields. While the demographic data provide one entry point, several of our programs are pursuing complementary research that can support greater understanding and more inclusive practices. Our Performing Arts Program, for example, participates with peer funders in related data coding projects specific to the arts sector and gathers county-level demographic data in the Bay Area to help guide how and where to build new relationships. Our Cyber Initiative is investing in efforts to better understand the demographics of the specific field it has been working to build at the nexus of national security and technology. Our Global Development & Population Program has been examining geographic patterns in funding—finding, for example, that just 20% of annual grant dollars were awarded to organizations based in Africa, Latin America, or Asia; with more intentional efforts, the program team raised that figure to 30% last year, and it has made continuing this shift central to its ongoing and future work.

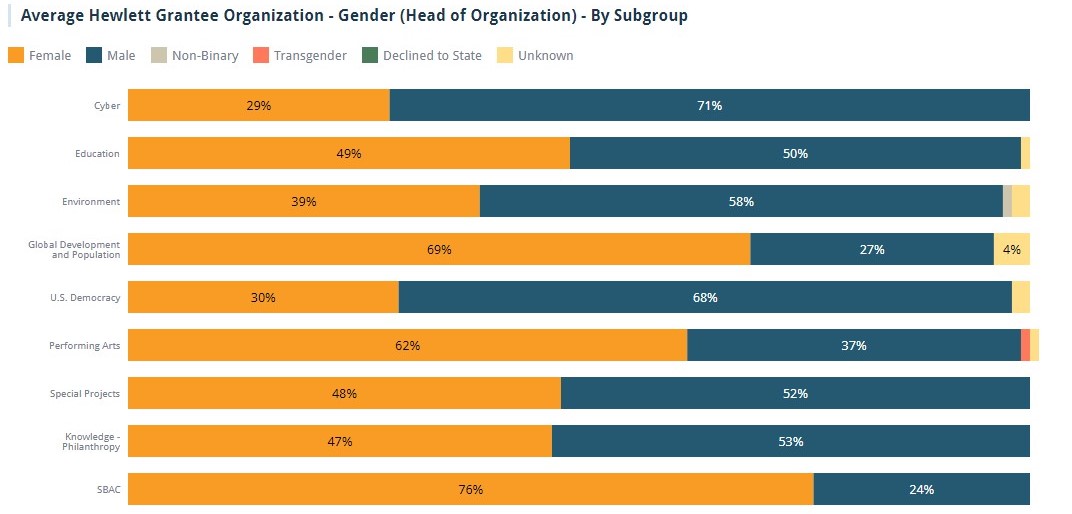

Expanding our networks to connect with new potential grantees and building deeper relationships with grantees serving diverse communities. Our Education Program, which has among the most diverse grantee portfolios in the foundation, is working to continue that trend with hopes of seeing, in future demographic reports, greater diversity on gender identity, increased representation of men of color at all levels, and increases in women on grantee boards and senior staff, among other changes. Considering new ways to source and build relationships with new grantees is a key consideration. For our U.S. Democracy program, the results of our demographic data collection has led the team to widen what has been a primary focus on ideological and political diversity to include more attention to race, ethnicity, and gender in its relationship-building, learning, and networking.

Provide capacity-building DEI grants to individual organizations. In addition to diversifying networks and building new relationships, Hewlett has for the past several years been making DEI-focused organizational effectiveness grants to existing grantees in all our programs. We know that all organizations, no matter how long or deeply invested in DEI, have room to grow and require support for capacity-building and restorative work. Although program staff receive the foundation’s demographic data in aggregate, they are able to use these data to explore how capacity grants for individual organizations might best be deployed to help organizations address challenges and long-term DEI planning.

Evaluating and adjusting grant practices that can introduce bias. Our program, legal, and grantmaking operations staff are exploring ways to spot implicit or unseen biases and ensure that our grantmaking operations function equitably for current and potential grantees. Steps here include exploring efforts to simplify Hewlett’s grant application and reporting process, use more requests for proposals (RFPs) and letters of inquiry (LOIs), and provide financial assistance to facilitate compliance with Hewlett’s legal and financial requirements. As one example, having observed in its data that grant investments in organizations led by women and people of color tend to be smaller, our Education team is making changes in the program’s due diligence and risk tolerance, so as not to create unnecessary barriers to larger investments.

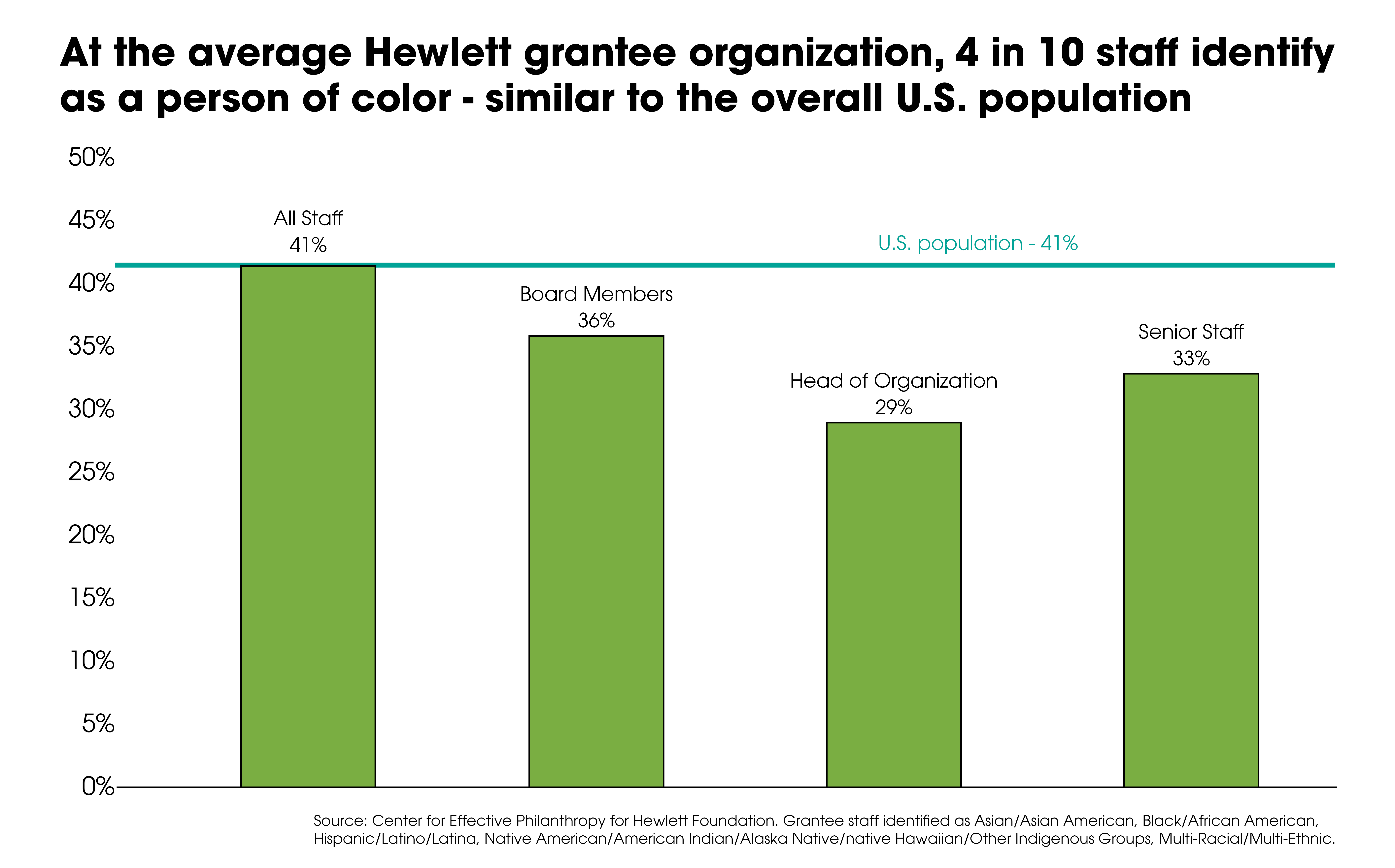

Supporting field-specific efforts to strengthen leadership and diversity, equity, and inclusion. Leadership matters, and these data help uncover gaps in specific fields and areas of work. Hewlett’s grantees with the smallest staffs are the most diverse, though, perhaps surprisingly, there is also considerable diversity—albeit to a lesser degree—at the largest organizations (400+ staff). In this U-shaped curve, diversity is most absent in organizations that have between 100-400 staff, meaning there are opportunities for program staff to help these organizations invest in, strengthen, and support diverse leadership. The data have also helped us identify specific fields in which to undertake more targeted action. Our Environment Program, for example, has made grants to support Green Leadership Trust, Latinos LEAD, and Race to the Board—complementary programs that work to create inclusive climate and conservation boards.

Considering the role of grantmaking intermediaries with respect to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Large philanthropies like ours rely on intermediaries—mission-driven groups that receive what amount to “block grants” that they re-grant in line with a shared strategy, especially to smaller organizations. Hewlett uses many such re-granting intermediaries, a product of our lean staff size relative to the scale of our grantmaking. To support, strengthen, and sustain diverse and inclusive grantee organizations, our programs have seeded and invested in intermediaries like the Climate and Clean Energy Equity Fund and the Hive Fund for Climate and Gender Justice. We are also evaluating whether and how well our other grantmaking intermediaries align with the Hewlett Foundation’s own commitments around diversity, equity, and inclusion, as well as those of the re-grantees. For example, our Global Development & Population Program has worked hard to ensure that re-granting organizations we work with in Africa provide general operating support and flow a substantial portion of the funds to many smaller advocacy organizations our grants are meant to empower.

Shifting our own language and supporting grantee-led efforts to amplify the voices of people of color and women. Our commitment to change extends beyond grant dollars and grant practices to reach other practices that may reflect or perpetuate inequities. We are exploring how to adopt asset-framing, championed by Trabian Shorters, in our language and materials, from strategy papers to grant applications, and updating our visual and text style guides to reflect more inclusive language. We are renaming our “Global Development & Population Program” to replace these outdated phrases, so entangled in the language of colonialism, with something that better reflects our values and the values of our grantees and partners. The foundation has also joined grantee-led efforts to promote more inclusive dialogue, as with a recent call to action from grantees of our Cyber Initiative seeking to change the makeup of voices in technology policy and national security events.

***

This is all just a start, and we know that much remains to be done. We will, undoubtedly, make missteps along the way. Describing ongoing efforts as a “journey” has perhaps become an overused cliché, but it’s apt here: we are working our way down a path in which we are learning with and from our peers, our partners, the communities in which we and they work, and the country at large. We do so with a good-faith commitment to do our best to do our part to dismantle embedded racism, bias, and discrimination in the fields in which we work and in our own culture and operations.

Explore the data, and view complete methodology and a summary of the findings from CEP.