Congress, help thyself

Congress will never be an early adopter. Innovations embraced over the years in other sectors, such as video conferencing, collaborative software, or teleworking, were often considered ill-suited to Congress’s type of work or security concerns.

Another factor is the decentralized nature of the institution, which makes it hard to advance consistent organizational practices. There’s no central human resources function, for example, though the SCOMC recommended one be created in the House. Each office theoretically operates as an “independent business,” but it also must comply with House rules about what equipment, programs, and outside technology services an office can purchase.

Steps to modernize Congress

Making information about Congress readily accessible to the public electronically has taken years. For example, until 2019, Congress.gov, the official one-stop website for Congressional information which gets one million visits a month, didn’t offer a calendar of committee activities (private vendors offered it for a fee). Until 2018, Senators still filed their campaign finance reports on paper with the Secretary of the Senate rather than electronically with the FEC like every other candidate. The Secretary then converted the paper to electronic reports and filed them with the Federal Election Commission at considerable taxpayer expense and delay.

At the urging of younger, more tech-savvy Members of Congress, Speaker Nancy Pelosi created the SCOMC as a short-term committee for the 116th Congress only. It was immediately embraced by Democrats and Republicans alike. Led by Chairman Derek Kilmer (D-WA) and Vice Chair Tom Graves (R-GA), it opted for bipartisanship over division. For example, the SCOMC had an equal number of Democratic and Republican members and a staff equally divided by party who worked together as one team. Kilmer and Graves insisted all recommendations be reported out with overwhelming, bipartisan support of committee members—a rarity in Congress today.

When the SCOMC began work, the knowledge and preparation of Hewlett grantees were indispensable. Almost a dozen of them coalesced into an informal working group that the committee relied on for help with identifying issues and solutions, historical background, research, and committee witnesses. Several consultants to the committee also came from Hewlett grantee organizations.

The impact of the pandemic

Then COVID slammed like a hurricane into a Congress that wasn’t prepared to work remotely, much less hold hearings or pass legislation virtually. The House ramped up, purchasing 1,000 new laptops in late February and helping staff upgrade their existing government laptops to work from home. New software, such as virtual meeting programs, were quickly approved for official use, a process that usually takes months or years. And rules were changed to allow interns to work off site and be paid.

Conducting official business, including committee work and floor votes, was more problematic. Initially, the House was reluctant to allow remote deliberations. But Hewlett grantees worked feverishly behind the scenes to show it could be done. They set up two virtual “mock hearings” online, one on March 23 and another on April 16, which featured retired General David Petraeus among the witnesses. Former Members of Congress acted as the “committee” and questioned witnesses remotely, without any significant problems. With this proof, both House and Senate committees soon conducted official virtual hearings of their own.

By May 15, the House had changed its rules to officially permit remote hearings and markups; and five days later, it allowed digital submission of bills, co-sponsorships, and statements for the record, which our grantees had advocated for years.

Congress also rejected outright the possibility of remote, electronic voting. But the House Administration Committee reported on November 10 that secure technology exists for it—something unimaginable last year.

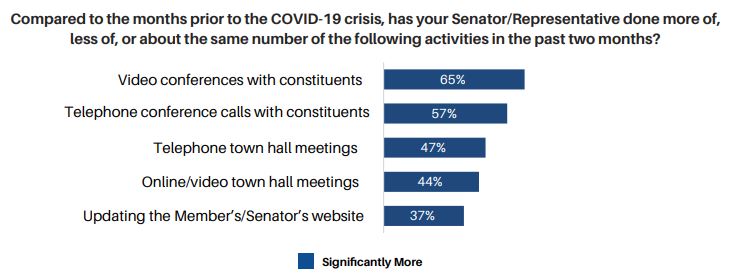

The pandemic also pushed the House to approve and Members to start experimenting for the first time with tech tools like Webex, Facebook Live and others that connect with constituents and colleagues in new ways from either their districts or DC.

According to “The Future of Citizen Engagement: Pre-COVID Challenges to Constituent Communication,” a report released in late October by the Congressional Management Foundation, most offices expect their COVID-created ways of engaging virtually with constituents to persist.