It’s the time for our annual performance reviews at the Hewlett Foundation, so I’ve been spending more than the usual amount of time reflecting on skills that my colleagues demonstrate at work each day. And that’s made me think about the special and somewhat peculiar qualities that go into being a good grantmaker.

The program officer’s job is a tricky one. This is the person who establishes a relationship with a prospective grantee and figures out where the organization and the project idea fit into the overall field that we support. The program officer has to gather enough information to have confidence recommending we fund the work, and weigh various factors to sort out both the level and the duration of our support. He or she vets proposals, monitors progress, connects grantees to each other and to other funders. It’s also the program officer who figures out when and how to evaluate grants or strategies, and when to recommend expanding a commitment or pulling the plug. Program officers are also members of a larger team and have management responsibilities, as well as the obligation of being a good citizen of a dynamic organization.

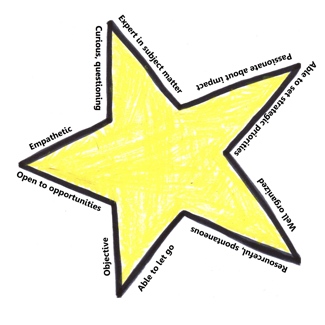

Program officers need to know a lot about their subject matter. In the Global Development and Population Program, for example, program officers have deep in-country experience and strong knowledge of the fields of reproductive health, education, governance, transparency and accountability, and gender. But sometimes they have to tell their inner expert to take the day off so they can question fundamental and often strongly-held assumptions within a field, and appreciate what people from other disciplines have to offer.

Program officers need to be well organized, able to keep to deadlines and tick tasks off a list. There are a surprisingly large number of tasks involved in grant making: the due diligence, the proposal review, the presentation to the Board, the report review, and so on (and on). If you looked at a program officer’s calendar here, you’d see at least 50 separate deadlines each year. (That’s about one a week, on average, and it often feels like one a day.) All too often, those fall when program officers are in a distant time zone, far from a reliable internet connection.

The pace feels relentless and the stakes can be high: missing a deadline almost always inconveniences many colleagues, and could even jeopardize our ability to award a grant.

At the same time, program officers cannot be so mired in planning and meeting deadlines that they are unable to respond when opportunities arise, there’s a need to act quickly to meet a grantee’s urgent needs, or a colleague needs a helping hand. And, while ticking the tasks off day-to-day, they still have to follow a separate, and very different, rhythm—that of keeping up in the field.

Program officers need to be passionate about impact, willing and even eager to ask hard questions of prospective grantees about how they are going to turn money into good things in the world. But sometimes—maybe even most of the time—they need to temper that passion with a willingness to let go, giving grantees latitude to do things their way. It is, after all, the grantees who are ultimately accountable for the success or failure of each grant. And people rarely do their best work when they feel that someone else is calling the shots.

Program officers are supposed to be “strategic thinkers,” able to set priorities for their time, grant and consulting budgets, and institutional voice. At the same time, they have to keep their mind open to opportunities that we might not have envisioned at the outset of the strategy—as well as to the possibility that things just aren’t working and it’s time to change course. Again, it’s a balancing act.

Finally, program officers have to tread a fine line in relating to people who benefit from a grant. Good grantmaking requires being able to establish a relationship of trust, one that entails empathy and connection. At the very same time, good grantmaking requires maintaining enough objectivity so that the funding relationship is sustained for the results, not for the relationship alone. That can be tough.

Five sets of skills, five ways to balance proactivity with restraint. Thinking in this way about how we’re all doing our jobs helps me understand what it really means to be a good grantmaker. And it’s permitting me to see many stars.