How non-governmental organizations can help institutionalize government use of evidence: Four possible paths

This is the third in a series from the Hewlett Foundation Evidence-Informed Policymaking (EIP) team on institutionalizing evidence use. We first described how we expected African policy research organizations could help make government use of evidence more routine. We then recommended focusing on government agencies’ routine decisions and the tools and practices that inform them. In this piece, we share what a number of our grantee partners are doing to help strengthen the capabilities, incentives, and systems for evidence use within government, as well as the external communities of practice that engage with government partners to facilitate more routine evidence use. This piece is also a companion to the EIP team’s recent open letter to grantees, Learning about Impact.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made painfully clear the importance of governments having and using timely, context-specific, and actionable data and evidence. Recent revelations about the transmissibility of the Delta variant among vaccinated people are just one example of rapidly evolving evidence that government officials must understand and react to. Throughout the pandemic, governments have faced a relentless pace of high-stakes decision-making about everything from infections, variants, and vaccine rollout, to understanding and addressing the pandemic’s effects on employment, food security, education, and more. All of this across geography, age, and race. The pandemic has put massive stress on the systems governments use to collect and share data and has, in many cases, revealed how outdated and feeble these systems are. It has tested governments’ ability to stay abreast of the latest evidence, and use it to make nimble, life-saving policy decisions.

As evidence use becomes more the norm, it can also make it easier for outside groups, such as think tanks or impact evaluation organizations, to promote the uptake of their research, or form new partnerships with government partners.

This constant evolution in both knowledge and policy priorities has been particularly rapid in the context of the pandemic but is not unique to it. For example, the World Bank’s Agriculture in Africa: Telling Facts from Myths initiative unpacks 15 commonly held beliefs about the agriculture sector in Africa, explaining where knowledge and evidence have evolved but practice has yet to catch up. For both government decision-makers and external data and evidence partners, this constant evolution means that using evidence must be an ongoing, routine, iterative, institutionalized practice.

Fostering an ongoing practice of evidence use within governments benefits both government officials and their non-governmental evidence partners. For governments, routine use of data and evidence to inform decisions can optimize scarce resources and lead to positive outcomes for people. As evidence use becomes more the norm, it can also make it easier for outside groups, such as think tanks or impact evaluation organizations, to promote the uptake of their research, or form new partnerships with government partners.

So, what role can outside groups play in changing how governments work with evidence?

The Hewlett Foundation’s EIP grantee partners are testing four approaches to fostering routine evidence use among government partners. They are working to strengthen the capacities, systems, and incentives inside governments to use evidence and data. They are also facilitating external communities of practice that support and nudge government partners in their use of evidence.

Strengthen Capacity

“Capacity building” can conjure images of one-way instruction in sterile classrooms far removed from day-to-day government decision-making. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Building on past challenges and lessons[1], a number of our partners are working in more creative, hands-on ways with government officials to bolster their capacity to use data and evidence. Claire Melamed, CEO of the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data (GPSDD), has a great thread about capacity building. She shares lessons from GPSDD’s work on the Africa Regional Data Cube about what it takes to strengthen government capacity to use earth observation data to support decision-making in agriculture and natural resource management. GPSDD has learned to focus not just on technical skills but also political engagement, regular peer exchange across governments, and embedding new tools and skills within existing agency governance structures.

The Africa Evidence Network confronts the power dynamics of “capacity building” in a Manifesto on Capacity Development for Evidence-Informed Decision-making in Africa. Explicitly countering the post-colonial image of foreign advisors filling African capacity gaps, the manifesto focuses on “existing capacities in individuals, organizations and systems,” while aiming to make “better use of local talent and capabilities.” It calls on partners to go beyond traditional training approaches and explicitly talk about power and equity.

Government officials also tell us they appreciate learning from and developing tools with their peers, and non-governmental organizations can facilitate this work. For example, Twende Mbele, a peer learning network of African monitoring and evaluation offices, is supported by a secretariat at CLEAR Anglophone Africa at the University of Witwatersrand. In addition to offering formal and informal coaching, members develop tools together, such as guidelines for conducting gender-responsive evaluations, and strategize about how to put them to use.

We also see promising signs that non-governmental organizations can support government colleagues in learning by doing. For example, the Ghana Institute for Management and Public Administration, in partnership with the Center for Effective Global Action, hosts training sessions for government officials interested in using impact evaluations to inform their decision-making. These sessions help government officials assess if an impact evaluation is feasible and would actually improve their decision-making, and if it would, then to find researchers to partner with. Part of the goal is to enable government officials to strengthen their capacity to commission evaluations and collaborate with external researchers on impact evaluations. This strategy has shown promise in the work of other institutions like the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation, J-PAL, and the Partnership for Economic Policy.

Several lessons emerge from these examples for non-governmental organizations partnering with government partners to use data and evidence.

- First is to start by understanding what government partners actually want to do and achieve, then helping find and use the evidence necessary to do it—akin to on-the-job training.

- Second is the value of learning from peers as GPSDD, AEN, and Twende Mbele are fostering.

- Third is the importance of going beyond individual skills to working with government officials to co-create the tools and organizational culture they need to make the evidence more routine, as Twende Mbele is doing.

- Finally, capacity strengthening shouldn’t focus only on how to use evidence in decision making but also on understanding concretely and endorsing the benefits of using evidence. This is where institutionalization starts from the inside.

With approaches like this, capacity-strengthening efforts can build demand for data and evidence, help open the door for ongoing partnerships, create enduring tools to ease evidence use, and make a focus on data and evidence more the norm among public officials.

Improve Systems

Changing “systems”—the tools, policies, and practices for evidence use inside government agencies—has the potential to make routine evidence use “stick.” Some of our partners make targeted efforts to strengthen a system such as data collection and analysis tools, requirements for budget impact analysis of new programs or evaluation of existing ones, or standing up dedicated evidence or evaluation units within governments. These targeted efforts can have a multiplier effect as that system is used to improve future decisions, even once the targeted initiative ends.

AFIDEP, with offices in Kenya and Malawi and partnerships with dozens of African governments, often takes a systems approach to its work. Over the years AFIDEP has helped the Parliament of Malawi build a first-ever budget office to regularize budget analysis in the parliament’s legislative and oversight functions. It helped the Parliament develop, adopt, and use guidelines for budget and bill analysis. It has worked with the Ministry of Health in Kenya to change data collection systems to disaggregate data by age and allow ministry officials to decipher for the first time the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescent women from those of older women. The AFIDEP partnership with the Kenyan Ministry of Health also helped secure more robust and routine funding for the ministry’s in-house research unit. (To learn more about AFIDEP’s work to help institutionalize evidence use across African countries, check out this presentation by Rose Oronje).

AFIDEP Director of Public Policy & Communications Rose Oronje shares more about the organization's efforts to institutionalize the use of evidence.

With agriculture as a priority sector for economic development and employment in Senegal, Initiative Prospective Agricole et Rurale (IPAR) recognized the acute lack of data tailored for policy decisions that affect rural communities. IPAR worked closely with the national statistical office to develop an agricultural data portal that was designed to increase access to, confidence in, and usability of data related to agriculture from both official government sources and non-governmental and private sector entities. In addition, IPAR worked with GPSDD, NASA, and the Ministry of Agriculture to access the Africa Regional Data Cube to use insights from satellite imagery. The goal is to fundamentally change how the Government of Senegal assesses the status of rain-fed agriculture and its relation to climate change as well as to complement existing survey data to track agricultural productivity, deforestation, and water resources.

Development Gateway (DG) has helped over two dozen ministries of planning and finance globally build country-level aid information management systems that enable these ministries to track where billions of dollars of donor funding are spent. DG and AidData have also supported many of these countries to collect detailed subnational data to track program locations by sector and funder. Governments can use the data to assess to what extent donor fund allocations meet national needs, and to encourage more effective and coordinated spending. For example, Nepal’s Ministry of Finance determined that the Far Western region of Nepal (one of the lowest income areas of the country) was relatively underserved by donor funding. They used these data to encourage funders to increase funding to this region.

This work to strengthen the systems that governments utilize to collect, access, analyze, and use data and evidence is about changing how governments work. As these examples show, a good place to start is on systems relevant for routine decisions, areas that government partners themselves have prioritized, or where champions inside governments can help open doors for external organizations to engage. This work increases the chances that data and evidence will be used in an ongoing, routine way if these systems endure even as people and specific policy priorities change.

Increase Incentives

Chris Chibwana, former Africa director for IDinsight, reflected on three years of working with governments to inform decisions with data and evidence. One of his big lessons is the importance of influencing how governments work rather than just what discrete decisions they make. He asks (and answers) these provocative questions:

“Are there one-off evaluations that others have conducted on behalf of governments that informed large decisions? Yes. Did they change any of the underlying causes of underperformance within governments, including the incentives for using evidence in decision-making? No.”

He highlights incentives as an important ingredient for ongoing, routine evidence use. But why are they so important?

One reason is because policy decision-making is non-linear, unpredictable, and influenced by many factors beyond evidence, including politics and power. We know this in theory. (For a great summary of the theory, see the literature review for the BCURE evaluation). And we know it in practice. For example, Ibrahima Hathie from IPAR in Senegal emphasizes the non-linear nature of policymaking and the importance of adaptability and political will in this presentation. So as evidence practitioners navigate through these unpredictable twists and turns of the policy process, they not only need capacities, they need motivation.

Ibrahima Hathie from IPAR in Senegal emphasizes the importance of adaptability and political will in policymaking.

How can one change incentives for government officials? Results for All compiled a set of cases about creating incentives for evidence use in governments, with examples from Mexico, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. These cases include a range of tactics such as an awards program for evidence use, transparency requirements about how agencies apply learning from evaluations, and evidence use as part of staff performance plans. Several of them include prominent roles for non-governmental organizations including media, EIP advocates, or training institutions.

Some of our EIP partners have developed awards programs as well, such as Africa Evidence Network’s annual Africa Evidence Leadership Award to celebrate evidence champions both within and outside governments in Africa. GPSDD motivates action first by inspiring high-profile political commitments. For example, they created the Inclusive Data Charter (IDC) to advance collection and use of inclusive and disaggregated data. IDC signatories not only publicly commit to the five principles of the charter, but take action as well. In some cases, these actions lead to important changes in data and evidence systems. Inspired by its IDC commitments, Colombia’s National Administrative Department for Statistics (DANE) recently formalized guidance for standardizing more inclusive, disaggregated data across the national statistical system. The new standards for “Differential and Intersectional Approaches to Statistical Production” are designed to bring DANE’s data collection in line with Colombia’s new legal and political attention to the differential impacts of conflict on various groups in the country—impacts that couldn’t be fully understood without better data systems.

We still have a lot to learn about what kinds of incentives have the most enduring impact: personal incentives like awards and performance plans; agency-based incentives like transparency requirements; or cross-country incentives through political commitments, charters, or even communities like the Open Government Partnership. We also hope that the incentive of better serving the public—both in terms of outcomes for people and increased legitimacy and credibility of government—will motivate government partners to use data and evidence to inform their decisions. All of our partners’ efforts recognize that extra motivation is essential for inculcating a culture of ongoing evidence use, given the many other pressures on policy decision-making.

Build and Be Communities of Practice

When we break down the elements of “institutionalizing evidence use,” we often focus on what needs to happen inside governments—capacities, systems, incentives to use evidence. However, building the habit of ongoing engagement with people outside of government is equally important. This means “institutionalizing” a practice of government officials seeking external input, evidence partners keeping abreast of policy priorities, and everyone building trusting relationships that enhance evidence use.

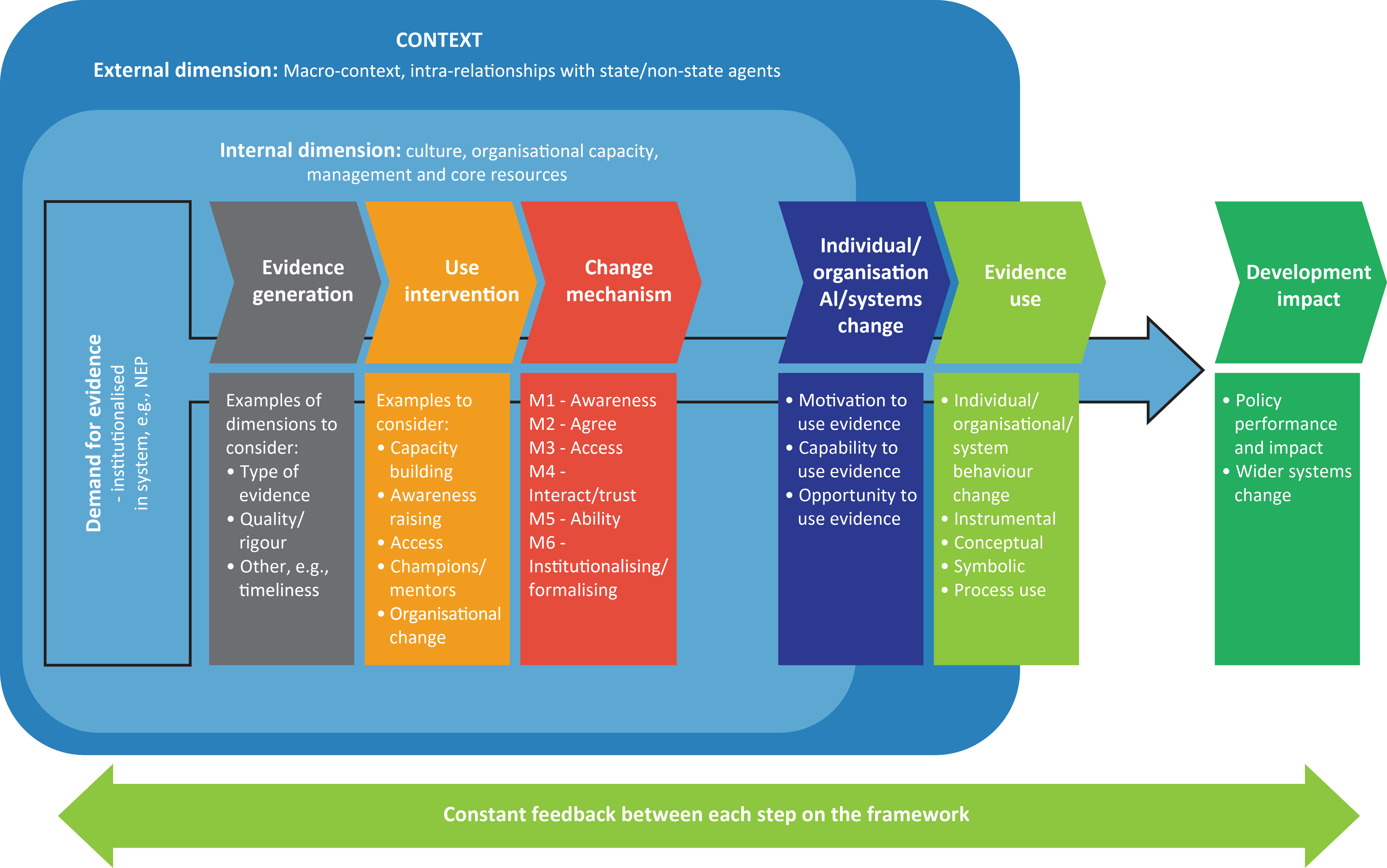

In Using Evidence in Policy and Practice: Lessons from Africa by Mine Pabari and Ian Goldman, the authors present an analytical framework for understanding how evidence use plays out in the policy process. In addition to the many important dimensions internal to governments, they also emphasize the external dimensions, including ongoing, trusting relationships among state and non-state actors.

From Using Evidence in Policy and Practice: Lessons from Africa.

Several of our partners foster this ongoing, routine interaction through “communities of practice,” which his central to the work of CDD Ghana. In collaborating with government officials at the district level, CDD explicitly includes this training objective: “Participants will learn how to develop relationships with other departments, CSOs and researchers to facilitate policy-relevant data and evidence production, sharing and use in policy planning and program management.” They explain it this way:

“Communities of practice are based on principles of social learning in that people do not learn in isolation, but by acting and interacting with others. Communities of practice can improve the generation and transfer of research evidence to practice by providing learning opportunities that facilitate interaction and information sharing among peers and partners, so that the use of evidence can be timely and context relevant.”

Utafiti Sera, a program of PASGR, builds standing communities of scholars, government officials, and civil society actors working together to bring research to bear on policy decisions. The Utafiti Sera “houses” are sector specific, for example in youth employment, social protection, or urban governance. This terrific conversation between Martin Atela, director of Utafiti Sera, and colleague Steve Koth highlights the importance of these communities and the trusting relationships they foster. These communities of practice help members navigate the politics associated with policymaking, can be responsive to both shifting policy priorities and evolving evidence related to these priorities, support policy implementation, and foster an ongoing “thirst for evidence.” Similarly, the Uganda National Academy of Sciences (UNAS) brings together government officials (particularly parliamentarians), members of civil society, and researchers to debate an issue in a neutral platform and come to a consensus position about the issue that Parliament is actively debating, drawing on synthesized and contextualized evidence.

Martin Atela and Steve Koth from Utafiti Sera highlight the importance of standing communities of scholars, government officials, and civil society actors and trusting relationships they foster.

We are seeing signs that, in addition to informing specific policy decisions (such as UNAS’ role in informing Uganda’s tobacco control policies), this kind of work can have ripple effects on government interest and capacity to use evidence and help build relationships that support ongoing evidence use. For example, PASGR is already noticing spillover from the specific houses into other policymaking areas. Thanks to the example of the Utafiti Sera house on urban governance in Rwanda’s capital city of Kigali, the government of Rwanda has invited the house members into a technical working group for secondary cities as well. This is a profound example of how strong communities of practice can support better policy decisions in their areas and also help foster a culture of more regular evidence use among government partners.

What happens next?

The work of Hewlett’s EIP partners to facilitate institutionalized use of evidence through capacity, systems, incentives, and communities of practice is encouraging. Yet, our partners and we are not sanguine about how challenging this work is, and how hard it is to make it “stick.” The AFIDEP team is frank in this presentation about the challenges, describing how hard it can be for civil servants to change their work culture and routinely use the knowledge obtained in trainings and related tools. Politics, conflicting interests, bandwidth constraints, and staff turn-over can hinder institutional change. And it can be really hard to understand the long-term impacts of this work since change is slow, while many partnership initiatives are time-bound. Some of our partners are testing tools to track downstream impacts of their work, for example this model to track downstream effects of capacity strengthening efforts (h/t Mawazo Institute).

We are also inviting our partners to consider “what happens next” after their direct engagement with government partners. We are encouraging them to assess how likely changes are to stick and why (or why not) using their own contextual knowledge and professional judgement. In true Hewlett fashion, we are taking the long view on difficult challenges, like changing how governments work with evidence, while also keeping a healthy impatience for signs of progress. Our partners are showing us that non-governmental actors have many opportunities to contribute to the sustained, routine use of evidence within governments. We look forward to learning, along with our partners, to what extent and under what circumstances these efforts to institutionalize evidence use contribute to more vibrant policy deliberations, better government decisions, stronger policies and programs, and ultimately better outcomes for people over time.

[1] For a great set of lessons about building capacity to use evidence, see the ITAD external evaluation of the UK Department of International Development’s £15.7 million Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE). The main finding is that where the BCURE partners took on the issues of politics, incentives, and systems—together with capacity, they were able to impact how governments use evidence. This blog from the ITAD evaluation team offers a great list of practical tips for making capacity strengthening efforts stronger.